THE

VOYAGE ALONE

IN THE

YAWL "ROB ROY,"

By JOHN MACGREGOR, M.A. CHAPTER XI.

High tides -- Seine pilots -- To bed -- Terrible scene -- A tumble in -- In the swell -- Novel steering -- The Empress -- Puzzled -- Night thoughts -- The start -- A draft on the deck -- Balloon jib -- On the deep

ON the Seine there is a tide phenomenon, called the barre, as in English rivers the bore, which when not provided for, is very dangerous, especially at spring tides. The water then rushes up the narrowing funnel-shaped estuary, in a broad and swelling wave, sometimes four feet high, and this will sweep off even large vessels from their anchors, and it causes many wrecks.

On a former occasion, when I happened to be in this neighbourhood, a high tide had been duly predicted by astronomers, which would culminate at the little town of Caudebec on the Seine, but would also rise higher than ever known before on all the adjacent coasts.

The news of this coming wonder spread over France, and there being then a lull in Europe as to revolutions, &c., except, of course, the perennial revolution in Spain, the quidnuncs of the provinces had to run to the coast for an excitement. Excursion trains, and heavily-laden steamers poured volumes of people into Caudebec, and many of them had never seen salt sea before, while even at the fashionable bathing-town of Trouville the sight was a strange one for a visitor.

Thousands of expectant observers paraded the soft white sand as the full moon shone on a waveless sea, and the brilliant dresses of the ladies coloured the beautiful tableau.

The tide flowed and flowed; it bubbled over the usual bounds of the shore; it trickled into the bathing-sheds ; it swelled still higher upon the trim-kept promenade, until it lapped the highest point, and then went gently down again. Eclipses and tides are patent proofs to the people that physical science can appeal to. The "music of the spheres" hath also a true rhythm, "There is neither speech nor language but their voices are heard."

To escape this barre on the Seine our steamer anchored by the quaint old town of Quilleboeuf with other vessels; and, though the wind howled and the rain poured, the hill beside us sheltered all from its blasts, which were too wild and powerful in the sea outside to allow us to proceed next day.

Frenchmen have a trick of anchoring thus to escape a breeze. I have seen them anchor on the African coast merely to avoid a hard-looking cloud, whereas the real danger was that they should anchor there at all.

However, our Seine pilot pointed to an English steamer "which dared not go out;" so any remonstrance on the subject was silenced, and then he boldly asked if I should like a pilot on board the Rob Roy (towed by the steamer all the time), and I had sufficient command of countenance to decline with due gravity.

Better, perhaps, it would have been for me not to be then so much of the John Bull in these strange waters, as will be seen from what occurred that night.

The tide rushed up with extraordinary strength, until it was quite full. Then it paused for five minutes, and again it set off in the opposite direction with the same fury increased, too, by the stream and the wind being also down the river.

At each of these changes every vessel, of course, swung round to its anchor, and so must have loosened their hold, while all the water picture changed from right to left like a shifted scene on the stage. During this short interval of quiet you could row ashore, but to get back again was almost impossible when the full torrent of water ran in straight. As night came on I noticed that our steamer's anchor was dragging, and that other steam vessels, more on the alert, were easing the strain on their cables by working their engines at half-power all the time.

"Captain, we are dragging anchor." "No, sir," he said, "you are mistaken." "I am sure we are dragging: I have watched for ten minutes." "No, sir, I am certain we do not drag," he said with such firmness, that I confidingly believed it and turned in to bed.

But it was not to sleep, except in fitful snatches. The sound of the water hurrying by my side, like a mill race, and within a few inches of my ear, had a strange and unwonted effect, not now to soothe, but to drive sleep away. Bits of wood and other debris often struck my mahogany sounding-board with a loud thump, until I became accustomed even to this, and was in a dreamy dozing about one o'clock.

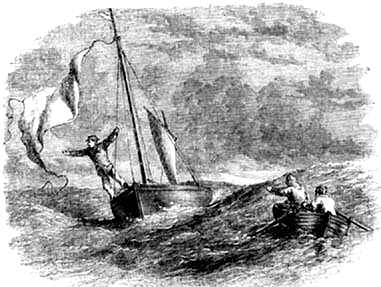

Then there came a new noise -- a low, steady rap, tap, tap, tap on the boat, and from underneath. For a moment or two there was sensation without apprehension -- a sort of mesmeric, irresistible spell; but a sudden thought burst through the trance, and with a powerful impression of what was doing -- one no less horrid than true -- I dashed off covering, roof; hatchway, and all, and stood on deck to meet a terrible scene.

Our steamer had drifted in the dark until we closed upon another steamboat astern. My yawl, tied to the stern of one, was between that and the bows of the other, the anchor chain of which had already got underneath the waist of the Rob Roy, and had been ringing the rap, tap, tap of a warning that undoubtedly saved her life. Light flashed from the riding lamp hanging at the steamer's bow full on my boat's deck, now heeled over deeply until the dark water rushed through her gunwale; and it seemed that only a few seconds more and the poor little Rob Roy would sink in the flood, or be ground into splinters by the two great iron monsters nearing each instant in the dark.

All this was seen in the same rapid glance which in such dangers grasps a whole scene in a moment and stamps it in the mind for years.

My boat hung on the chain, yet wavered with equal poise to go this way or that. If she could be swerved to the stern she might possibly escape destruction, but if to the other side, then the strong rope at her bow would entirely prevent her escape. With a loud shout to arouse the crews I put every atom of force in my body into one desperate shove, straining nerve and muscle in one desperate effort until I could not see. She trembled and surged -- it was successful, and I fell into the water, but my yawl was saved.*

Crash came the two steamers together I heeded nothing of their din and smashing, and the uproar of the men, but I had scrambled all wet into my cabin, nervously shaking with excitement and a chattering of teeth. Then I sat down to sum up my bruises -- a barked shin, sprained thigh, and bleeding cheekbone; and a hapless object I must have seemed, bathing by turns, my leg, and shin, and face, from a brandy bottle, and then a gulp inside. A survey of the yawl was made next day by placing her on the gridiron at Havre; and when the tide left her dry, there was to be seen (as still there is) the marks of the iron chain links impressed deeply in the mahogany planks of her waist. The piece of wood that bears these mementoes of that night's deed might well be cut out and kept as a curious memorial. The bowsprit also was found to have been nipped at the end (though it had been drawn in close to the stem) and the squeeze had quite flattened the strong iron ring upon it, and jammed up the wood into a pulp as if it were cork.

* See frontispiece.

The weather did not moderate next day, but we started nevertheless, and when the waves of the wider sea were tumbling in I expected to have a wetting, as in passing here before; but the sea was in fine long swells, and so the yawl rode over them buoyantly. Also the large twin-screw tugboat is far more pleasant to follow than the smaller steamer with its two paddlewheels, one at each side of the stern.

This latter construction is found to be very convenient because the cargo is at one end of the vessel and the machinery, and paddlewheels, and steering apparatus are all at the other end, so that orders can be readily given to both by the captain. The "Express" Company on the Seine has sixty of these steamers.

In another way also I managed better than before while undergoing the process of being towed. I set the hatch of the well in front of me, and then allowed the reflection of the funnel of the steamer upon the wet deck of my boat to be seen through a chink, while my head and body were entirely concealed and completely sheltered from spray.

Now, having marked where this reflection rested, when I was exactly in a proper line abaft the steamer, I was enabled to steer altogether by the reflection, although I could not see the object to which I was directing the bow of my boat. The captain and crew of the steamer were very much astonished with this proceeding; but it was an adaptation of the same principle I had used in Swedish lakes, when my course was towards a bright sun so dazzling in the water that I invented the plan of covering my eyes with my straw hat and steering the canoe by the bright reflection of the sun on its cedar deck, which was of course by no means so unpleasant as the beams of light glancing from the water itself.*

Arriving at Havre on July 21, there was need for a good rest and the port was well suited for it. 'There is quiet water in a sequestered nook of the harbour and plenty of amusement on shore. Havre, too, was in a state of much excitement, for the Empress was about to embark thence for England, and the Imperial yacht was in the basin, with a splendid crew on board. In the evening the Emperor also came to the town, to escort his wife when she embarked, and as his carnage drove past the crowd ran after it hallooing.

The last time I had seen the Empress Eugénie was under somewhat peculiar circumstances; she was floating in the sea, and we shall tell more of her Majesty in a future page, when fair bathers at Margate appear.

* Surely it would not be impossible to make the needle of a manners compass itself steer the ship at least within half a point. 'The motion of the needle could connect one or the other of two electric currents, and so set in instant motion a powerful purchase to act on the tiller.

The beautiful English yacht 'Vindex' was on the gridiron with the Rob Roy; that is to say, on a sunk stage of wood, on which you can place a vessel, if it is desired to examine or repair its hull and keel when the tide leaves it there dry.

'Vindex' had come to the Havre Regatta, and as she had won the prize there in the previous year a great deal of interest was shown about her now. But the regatta on this occasion was by no means interesting, as the wind fell into calm, and it was merely a drifting match.

My usual visits in the dingey had disposed of nearly all my store of French books and periodicals, and the remainder we took to a civil bookseller, from whom we bought French charts and a Pilot book of the English south coast soundings.

Meantime, after a rest and refreshment to my crew, a thorough scraping to my boat, and a good stock laid in of comfort for my voyage to England, the question had to be distinctly put "How am I to get over the broad Channel to the Isle of Wight?" It was, of course, impossible to think of coming back as we had gone -- that is, along the French coast. This would never do. Again we found that the steamers were not allowed to tow any boat to sea behind the passenger vessels unless in case of distress, so that put an end to another solution of the problem, which was to get half way by towing and then to cast off and sail.

Then shall I get an additional hand on board? But where is he to sit if it blows hard ? If it does not blow hard, what is the use of him? In fact, I was gently driven, as if by severe logic, to the conclusion already at the bottom of my mind, to sail right across alone. Then I asked one or two experienced sailors if they thought the Rob Roy could do it, and they said, "Yes, she can; but can you? You may be three or four days out, and can you stand the fatigue? At any rate, do not start in a south-west wind: it raises a sea, and the up and down of the waves will tire you soon in a long day's work, and then comes the night besides."

Then I retired to my calm little creek, where the yawl was tied by a line to a large fishing smack, and I tried to read, but soon found I was thinking of anything but the words on the printed page; then to sleep; but still I was musing on the prospect now opened of a hazardous but delightful sail.

About one o'clock I gazed on the quiet night scene of the harbour, sleeping around. Tail masts whitened by the moon, black hulls darkened in the shadow, busy quays silent, long-necked iron cranes peering into the deep water, that reflected quaint leaning houses, all distorted, and big buoys magnified by the haze.

"Why continue this anxiety as to how to get over? See the clouds drift over the clear moon with an east wind. Will it ever be easier than now? I cannot sleep -- why not start this moment?"

Once the decision was made, all was alert on the Rob Roy; and in half-an-hour I had breakfasted, and then very noiselessly loosed the thin line that bound her to the quay, and bid "adieu to France."

Every single thing I could think of was perfectly prepared. My sails were all ready to set, but I had to row the yawl slowly into the main harbour, and there we met a low round swell coming in from the sea. I tugged hard to force her against the adverse tide, but progress was tediously slow. Now some fishing luggers were getting under way, and soon the usual clatter and din of the French sailors, at full tide, rang forth as if by a magic call at two in the morning.

After shouting some time for a boat to tow me to the pier-head, at last one came. "What will you charge?" "Ten francs." "I'll give you eight;" and after parley the two men in their little boat agreed to take the Rob Roy in tow.

Almost immediately I observed that the moon was hid, and the wind had chopped round to the south-west the very wind I was told not to start with, but now -- well it was too late to withdraw, and so we laboured on, while the great clumsy luggers crossed and recrossed our course, and frequently dashed upon the piles of the pier in the stupidest manner, with much loud roaring of voices, and creaking of spars, and fluttering of sails.

Presently the men called out that, as the sea was getting higher, I had better pay them the money. "Certainly;" I said; but, alas! could find only five francs of change, the rest being napoleons.

They shouted, "Give us gold -- we will send the change to England;" but I bellowed out a better plan, to give them an order on the yacht agents at Havre for five francs, and the silver besides.

Finally this was accepted, so I got out paper and envelope, and on the wet deck, by moonlight, wrote this banker's draft.

When they came near the harbour's mouth, they sung out, "Get ready your mizzen." "Aye, aye!" "Hoist !" and so up went the trim little sail, glad to flap once more in salt air. Then they bid me, "Get ready your jib -- we have cast you off; hoist!" Yes, and I did hoist.

Perhaps the reader may recollect that the end of my bowsprit had been squeezed by a collision, and was in fact as weak as a charred stick. But I had entirely forgotten this, by some unaccountable fatality, during the three days at Havre, when it might have been easily repaired.

Balloon jib [166]

The moment therefore I had hoisted the jib, the bowsprit end broke sharp off into a ragged stump, and the jib instantly flew away into the air, just like an umbrella blown inside out.

This was of course a most critical time for such a mishap, with a strong breeze dead ahead, driving me in upon piles, and a tumbling sea, and numerous large luggers sailing about me in the dark. Therefore I felt that this unlucky accident, and the south-west wind meant, "I must not go out to-night. It will not do to begin a voyage of a hundred miles with a broken bowsprit."

All this prudent reasoning was at once cut short by the Frenchmen calling out "Voulez-vous sortir encore, monsieur ?" and the Rob Roy thus hailed could make but one reply, "Oui, oui certainement;" so I bid them lay hold again while I captured the truant jib, hauled down and reefed it, and made it fast to the stem, and then again "Laissez tous," and we are free on the rolling waves.

At the worst, I could return in four or five hours, when the tide fell, if I found it unadvisable to go on; but meanwhile I shot away westwards, to get a good offing from the Cape de la Hève , and then cooked breakfast (the former one counted of course in the former day, according to the excellent rule already explained), and about half-past four I laid on my straight course to old England, with a capital breeze on my quarter, and a hundred times glad that I had not gone back.

CHAPTER XII.

Nodding -- Prancing -- First thoughts -- Present crisis -- Midchannel thoughts -- Battle -- Church

UP rose the sun, and all was cheerful. Then I laid her to, and got out my axe, and chopped the bowsprit into shape, so that it would run out further, and then set the whole jib firmly on it.

All the feelings restrained so long by the river work, and regatta amenities, and Exhibition in Paris, now came forth powerfully in a flow of enthusiasm.

Boys seem to like the story of the canoe voyage, and perhaps they will read this one of the yawl. If they have a sailor turn, they will imagine the new pleasure to be felt when you glide away from a fast-retreating land, and nothing is in front but sea, sea, sea. Then the little boat you are in, and know in every plank, and love too becomes more than ever cherished as a friend. It is your only visible trust, and, if it is a good boat, you trust it well. It seems to try its best, like a horse on the desert plain, that knows it must go on if it is ever to get to the other side; and as the cliffs that looked high behind you, dwindle into a line of deep blue, the compass by your knees becomes a magic thing, with no tongue indeed to speak, but surely a brain it must have to know the way so well.

For hours we went on thus in silent pleasure, gazing at the gentle needle as it moved without noise; and, with nothing around but plash of waves, bright sun, and a feeling of hot silence, the spell of sleep was overpowering. Homer sometimes nodded, it is said, and he would have certainly had a good nap had he steered long thus. The sinking off into these delicious slumbers was imperceptible, and perfectly beyond the will's control. In a moment of trance I would be far away in dreamland, and with a thousand incidents, all enacted in orderly succession, with fights, wrecks, or pageantry, or the confused picture of bright-coloured nothings which fancy paints on the half-alive brain.

From these sweet dreams there was a rude awakening; a slap from the sea on my face, as the yawl, untended, suddenly rounded to, or a rattling taptoo on the deck when the jib-sheets found they were free.

Then for a time I would resolutely insist upon attention -- every moment of slumber being a positive wandering from the course; but no, the outer self that demands a nap will not be denied by the inner nobler self that commands alertness.

Only one single seagull did I see in thirty hours. One vessel also far off was the sole break upon the painfully straight horizon, and as the wind gradually died away into nothing, the prospect did not improve.

Then came the up and down, riding over seas without gaining a yard, the "prancing" of the vessel which had galloped forth in the morning like a horse in its first bounds on grass when, leaving a hard road, its hoof paws gladly the springy turf.

The thoughts that came up from recesses in the mind were new, but too new and unnamed to put in words. Alone on the waters, when you cannot see land, is a strange condition. But if only fog or darkness hides the land, you still feel land there. Quite another thing is it to be afloat alone, where, because it is fifty miles away, land cannot be seen. Doubtless it may sound foolish, but I am not able to tell the feelings of that time.

Becalmed midway between France and England, it was natural for the mind to think of both countries. Every time I have left France it has been with more admiration of it. First thoughts of people and of countries are more striking, no doubt, but only by chance at all true. I recollect asking an American, after his visit to the English House of Lords, what struck his attention most; and he said, "Their lordships don't seem to brush their hair." Another clever traveller, from the same land of our cousins, was asked what he noticed of our manners in London, and he replied, "I observe it is the fashion here, when a gentleman sees his friend on the other side of Pall Mall, he shakes his umbrella at him, and calls out, ''D'ye do, old fellow?"'

In looking at Frenchmen, during this visit for the twentieth time, it seemed to me -- but very likely much of this was in fancy -- that they showed evident signs of wounded vanity, that they were conscious of playing second fiddle in the grand opera led by Bismarck; but I need not stop in the British Channel to meditate on the political future, while France will have taken huge strides into it long before these lines are read, and in what direction no seer could say.

As for England, does any one recollect a time which was not spoken of by some one or other as "the present crisis"? Perhaps you ask, "Crisis in what?" and one will answer, "Oh, of course, the money market," or politics, or corn.

If there is now a "present crisis" in religion, it has a feature that can reassure; religion is at least more considered than ever before. It may be opposed or misapprehended or derided, but it is not ignored by so many millions of Englishmen as it used to be.

Look at the three leading newspapers, the morning, the evening, and the weekly registers of the direction, warmth, and pressure of public thought, as noted by keen observers, who are shrewd and weatherwise as to the signs of the times, and are seldom wrong when they hoist a storm signal. More end more each of these secular papers occupies its best columns with religious questions, and not with the mere facts or gossip on the subject, or with records of philanthropy, important as these are, but with deep, essential doctrines, and prolonged arguments about the very kernel of truth.

Religion is allowed to have a place now in every stratum of society, even if a wrong place and a very uncomfortable place for a slender religion. Sometimes, indeed, a politician laments that "Parliament has its time occupied by the subject," as if it were possible for the House to settle the Church and the School and the homes of men, without also considering their religion.

And if almost each family gives some place or other to it, so perhaps no one man in England would allow any other man (besides himself) to say of him that he had nothing to do with religion.

The Christian religion is more questioned than ever, if only because there are more questioners. Nearly all of these, in England at least find it convenient to admit one point to start from "There is a God," be He styled in redundant reverence, "Nature," "Providence," or "Heaven." The vacuity behind that is too dark and abysmal to be a home for any soul, and therefore they will accompany you thus far. This short creed is long enough to cover many different meanings, and elastic enough to be worn, at least outside, by all, for common decency, while it will also fit upon almost any form of life and character.

Some men have never had more than this meagre garment. Others have been swathed in more ample folds from the nursery, but have stripped off the mental clothing of their childhood, feeling it tight, or encumbered with braid and tassels, and have torn it all to tatters; at last, as their inner being soon chills in the air of naked freedom, they take on them this creed as the one general raiment of prudence.

There may be quiet in this, if not comfort; for the garment fails to warm the heart, if indeed it even covers the head. But the mind soon wondering whether God can be, and yet not do, and it yearns to know what God has said and done. Instinct tells it that to know the very truth upon this will make the man's creed a vascular body for action, not a mere decent clothing. "Yea hath God said?" was asked in Eden. Christ, on the contrary, asks, "Wherefore do ye doubt?"

The mind begins its search for truth in unquiet times, and on a battlefield. It is a fight rather than a search. Facts and testimony have to be settled, and in hot conflict, which are felt to touch every point of life, and not mere fancies too high in the air, or thoughts too deep for common people. Each man has to be fought hand-to-hand here. Strategy and leaders avail not. Mere numbers on one side or the other do not count for individual conviction; we are not saved in bundles.

No man can keep out of reach of the turmoil, though many would be content to remain as bystanders, secure from remark or disturbance, in a hazy cloud. They are distinct only in their denial that there is anything definite. Still they have a religion with their undescribable creed. Their creed is not strengthened by being curtailed. " Moral sense," "intuitive truth " -- their ultimate appeal -- is just as little deduced or proved by algebraic logic as any of the propositions are which they reject because these cannot be proved thus. Try it by their own standard of proof and it shrivels away, until no God -- no soul -- no being remains as absolutely demonstrated, except perhaps each man faintly conscious of his own existence.

There are others who, frightened by the hurly burly, after a short wild wandering alone in the din, join any group, as a refuge, if it be only visible, and so a Church becomes an asylum for the timid rather than a fortress for the brave.

God seems to "shake terribly the earth," and the Church that is nursed and dozing ill the lap of the State has been roughly shaken, but is not yet awake. She has grown, in bulk at least, while sleeping. Is she not like an overgrown child too big to be carried, and too rickety to walk alone?

For some time our Church has been not National but Diocesan, with different doctrine and worship in different dioceses. The bishops meet, and thinking different, but trying to say the same, they say what is only unanimous when it means nothing. Each parish next will judge of the ribbons to be worn as badges of its doctrine. We are crystalizing into congregations, and soon these will split into families, and so perhaps we shall get back at last to the simple old shape, when the message was for Nymphas and "the church which is in his house."

And as individual convictions are searched and purified by trials which seem to dislocate all the fabric of a man's faith, but only to enable him to begin building aright, not upon creed nor church but upon Christ so may the now shaken pile of our Church be raised higher, purer; and stronger, after all its outside pilasters have been cast down, and the cornerstone remains alone firm, a flock.

CHAPTER XIII.

Half-seas over -- Thick night -- Risky -- Reckless -- Tied in -- Lying to -- Land ahead -- Scottish replies -- Sleep

NOW the sails are impatiently flapping. Each wave jerks the mast and canvas with a smart loud crack like that of a whip. The sound is unspeakably irritating, it seems so useless and wanton, and so perfectly de trop while the wind is absolutely calm. At other times, in such a case, you can stop this provoking clatter or moderate it by hauling up the boom and lowering the jib; but here, in mid ocean, we must be ready for the first faint breath of wind, and moreover -- best to confess it -- I had a serious disturbance within, yet not mental. Strawberries and cream imprisoned with mushrooms did not agree.

They called them mushrooms in Havre yesterday, and we know "there are 731 edible fungi;" but I assert that the rebellious species embarked with me were toadstools, and so giddiness followed upon sleep

Gentle and cool is the first fresh murmur of a new breeze as it comes from afar, tripping along. Gratefully we watch its footsteps on the sea. Its garments rustle in the south, and the once round glassy waves are now crested by its touch. Then the flag flutters while the sails fill full, the mast yields under the soft pressure, and the Rob Roy runs eagerly again upon its proper course.

Dinner was instantly served up to celebrate the event. It is an Englishman's way. Still we were fifty miles from England, but wave after wave rose, dashed, and was left behind, till the sun got weary in his march, and hung, in the west, a great red globe. My course had been taken for the Nab light, which is in the entrance towards Portsmouth, but the Channel tide, crossing my path twice, would carry the yawl fast, yet secretly, first right, then left, and both ways once again.

Yet when the evening shade fell we expected to see at least some light in the horizon, for the English lights are clear, and they shine out twenty miles to sea. How I peered into the inscrutable darkness, and standing by the mast to get higher, but in vain; yet still the wind urged on, and the sea tumbled forward all in the right way.

Hours passed, and ship-lights now could be descried; they were crossing my path, for they were in the great fairway of nations bound east or west through the Channel. This at least was company, but it was also danger. We have left the lonely plain, and are walking now in the street of waters; but how am I to sleep here, and yet I must sleep this night. I tried to "speak" a goodly vessel sailing past like a shadow -- I ventured even too near it -- hailing, "How far to the Nab?" but the voice melted in the breeze. Low vapoury clouds began to rise from the sea; they looked like dark trees around; but the stars were clear up above. It was impossible to feel as if land was not there, yet when my lead was cast the deep only laughed at its little reach downward.

In such thick weather it will never do to ferret out the channel to Cowes, even if we are near it. The night must be passed at sea, and better do that now than go in too near the cliffs in darkness, and so we prepared to lie-to. Lowering the mainsail I tried her first under mizzen and jib; but the rolling in every trough of the waves was most uncomfortable, and besides she drifted north, which might end by going ashore.

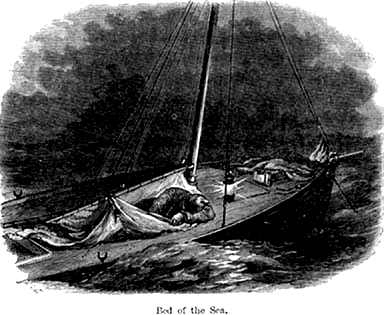

Then I took in the jib and set the storm mizen, and hung out the anchor with twenty fathoms of chain -- not, of course, to reach the bottom, but to keep the boat's head easier in the sea, and this did perfectly well. The motion was a long, regular rise and fall, and the drift was to the east; quite out of our proper course, but I couldn't help that ; now I must make my bed. Undoubtedly this was a risky deed about to be (lone; but pray what else could we do?

"You ought not to have come there at all," may be replied.

Say that to the huntsman who has got into a field with the only way out of it over a chasm to leap. Tell it to the mountain climber scrambling down, who pauses before a crevasse; and (10 not forget to say the same to the poor old fisherman overtaken in the midnight winter's gale, with his life in one hand and in the other a tangled net that has caught the fried sole for your comfortable dinner.

It would not do of course to go into my cabin. In the first place, the dingey was there, and then if I were to be enclosed inside when anything like a "run down" had to be dealt with, the cabin might be my coffin.

First I tried to crouch down in the well, but the constraint on limbs and joints was unbearable. My head slept while my knees ached with the pressure. No! there must be a positive lying down to sleep, if the sleep is to give true refreshment when you are rocked about on the waters; and this you have no doubt been convinced of any time at sea.

The strange twists of body I tried to fit into comfortably where the space was only three feet each way, reached at last to the grotesque the absurd contortions of a man miserable on a sail for pleasure -- and I laughed aloud, but somehow it sounded hollow and uncanny.

One effect of extreme exhaustion is to make the mind almost reckless of risk, and we can well understand how in some shipwrecks, after days Sand nights without sleep, men are in a placid, callous composure of sheer weariness, and that the last agony of drowning then is nothing, just as Dr. Livingstone tells us, the shake given by a lion to its victim paralyses the whole system before it is killed. Therefore, as danger was only likely, and sleep was imperative, I loosed out the folds of the mainsail. How white and creamy they looked while all was dark around, for no moon had risen. Then I put on my life-belt, and fastened the ship's light where it would not swing, but rested quite close to the deck. I rolled the thick, dry, and ample mainsail round me, stretching my limbs in charming freedom, and I tied myself to the boom, so as not to be easily jerked overboard by the waves. Of course it was my firm intention to sleep only by winks of one eye at a time; but the struggle with Morpheus was, we suspect very faint; at any rate no record remained but a few dim visions that may have flickered in the soft vanishing of consciousness.

Bed of the Sea [182]

The motion of a vessel lying-to is far more easy than what would be supposed possible. When you are rocked in a boat making progress by sails or steam, the pressure of each wave is more or less of a blow, for the ship is going forward, and it resists the mass of water often with violence. At anchor, too, though in a modified degree, the same is the action, and in a swell without wind the oscillations are jerky and short, for they are not softened by the sails then merely hanging. But if a boat is staunch and strong, and the deck is tight, and she has plenty of keel, so as not to swerve round right and left but to preserve a general average direction towards the wind, then she may lie-to in a very stiff gale and high sea with a wonderfully gentle motion. Her head then is slightly off the sea, and there is but little rolling. The sails are so set that they ease every lateral heave. She forges forward just a little between the wave tops, and when the crest of one lifts her up she courteously yields for the time, but will soon again recover lost ground. This is the very epitome of a well managed "compromise," and when I saw how admirably the Rob Roy behaved in lying-to, and that scarcely a wave broke over her deck, I felt that if it came to the worst we might thus pass a whole week in her safely. As to where she was at this particular time I had of course no possible idea, but judging from after circumstances, the spot must have been about ten miles south of St. Catherine's Head, and she drifted twenty miles east while I dreamed.

Can any person be expected to describe his first feelings as he awakens in such a bed and finds it broad day? Bright and glorious sun, high up, how I stared at you! and then a glance to the side, and behold, there is land -- England. Deliberately I rose and gave three hearty cheers -- nobody there to hear, indeed, but me -- no matter, it did good to me to cheer, and to hear too. Breakfast was soon agoing. Ten hours' sleep had thoroughly refreshed me, mind and body; but I could not make out what part of the coast we had hit upon.

It was still about twelve miles distant, but there were no cliffs, so it could not be the Isle of Wight. My chart told nothing; my French Pilot-book had woodcut pictures of all the coast, but nothing came of the search in these; and whether we had drifted east or west of the Isle of Wight we finally gave up as a book question -- we must go to the coast itself and see.

Therefore we steered due north, rapidly nearing the unknown land, and with a joyous morning, barometer high, wind south, and a coming fine day. Presently there loomed on the horizon one, and then another, and another, splendid ships of war. They steamed in line, and I tried to intercept them to put the query, "Where am I?" Baffled in this, the puzzle was, "Are they going to Portsmouth or Plymouth?" There were equally good reasons for either.

At length three towns could be seen, and the pictures of the French Pilot-book were closely examined, but several plates had each three towns which would fit the case before me, one as well as the other. Fortunately we chose the middle of the three, because it had a little lighthouse. That on the left we found afterwards was Bognor, which has a reef of dangerous rocks on its shore.

A fisherman was in his boat and I hailed him,

"Boat ahoy! What is the name of that town?""Town, sir?"

"Yes; that village right ahead; what do you call it?"

"The village there, sir ?"

"Yes; what is its name? It has a name, hasn't it?"

"Oh, yes, certainly, sir, it's got a name."

"Well, what is the name? I don't know where I am."

"Where have you come from, sir? from the Wight?"

And, after these Scottish answers to the questions of a Scotchman, at last I found my way into Littlehampton; and if ever you go to the Beach Hotel in want of a soft bed, after sleeping out of a bed for nearly a month, you will find it there.

This little place between Bognor and Brighton, is a quiet bathing town just in the delicate stage of existence, when it has been found out and admired, but not yet spoilt. One row of houses fronts the sea with a fine grassy plain between, and a clean white strand.

The Inn is of olden times, and apart near the water, with a landlady of the good old English type; and her son, the waiter, rampant about canoes, keeps an aviary under the porch and a capital swimming dog in the stable.

Lie on a sofa in the coffee-room detached, and read the Times -- go into the drawing room and play the piano, or sit under the garden trees and gaze on the fair blue sea, and hope fervently that, with a strong Tory government to protect our institutions, this hotel may be long kept hid from that merciless monster the "Company (Limited)." But already a railway runs here, and threatens its retirement. Even a steamer now and then from France screws its way into the very narrow channel, and the river Arun has wound down thus far from Arundel.

© 2000 Craig O'Donnell

May not be reproduced without my permission.