Alone in the Caribbean

CHAPTER VII

DELIGHTS OF CHANNEL RUNNING --

JOSEPHINE IN SAINT LUCIATHE NEXT morning, March 30th, found me once more in the Yakaboo rowing out of the bay of Château Belaire half an hour after sunrise. The night had been an anxious one on the morgue-suggesting cot of the rest room in the police station -- for the devilish impish gusts had swept down one after the other from the Souffrière and shaken that house till I thought it would blow over like a paper box and go sailing out into the bay. If those fellows caught us in the channel what would the poor Yakaboo do?

I argued that the wind coming down the smooth plane of the mountain slope and shooting out across the water had developed a velocity far greater than anything I should meet in the channel. Perhaps so -- but I should learn a bit about it later. I somehow bamboozled my mind into quiescence and at last fell asleep. Almost immediately the big, burly Barbadian awoke me. In an hour and a half I had rowed the six and a half miles to Point DeVolet, where I set sail.

I was now started on my first long channel run and it was with considerable interest if not anxiety that I watched the canoe and the seas. I had a lurking suspicion that I had made a grievous error when I had designed the Yakaboo ; I had perhaps erred on the side of safety and had given her a too powerful midship section in proportion to her ends. That was the feeling I had while sailing in the channels of the Grenadines. I was still traveling eastward as well as northward, and I knew that it would only be by the most careful windward work that I should be able to fetch the Pitons, thirty-one miles away. The wind on this day was the same trade that I had met with lower down, but the seas were longer than those of the Grenadines, and, if not so choppy, were more vicious when they broke ; there would be less current to carry me to leeward.

I had scarcely got her under way and was still under the lee of the land when the first sea came, like the hoary hand of Neptune himself and we turned to meet it. Aft I slid, she lifted her bow -- just enough -- and the sea broke under us -- and we dropped down its steep back, with lighter hearts. In with the mainsheet and we were off again, the canoe tearing along like a scared cotton-tail -- a little white bunch under her stern. There was something worth while in this and I kept my eyes to weather for the next sea. Again we met it and came through triumphant. Perhaps I had not erred after all. Another sprint and so on.

After a while the Yakaboo seemed to lag a little and hang her head like a tired pony. It was the forward compartment that was leaking again and I ran her into the wind, dropping the jib and mainsail. The little mizzen aft, flat as a board, held her directly into the wind's eye (which I believe is the best position for a very small craft hove-to), and I could go about sponging out the compartment.

I had, of course, to keep a sharp lookout ahead for breaking seas. If a sea threatened, I would hastily clap on the forehatch and give the screws a couple of turns and then roll back on my haunches into the after end of the cockpit. My precious camera was lashed half way up the mizzen mast. Lightened of the water in her forehold I would hoist the mainsail and jib and give her rein, that is, trim her sheets for another scamper to windward. She was the spirited pony again.

That we were traveling well there could be no doubt. The wind was blowing at least twenty miles an hour and the canoe was covering her length with the smooth action of a thoroughbred. Yet when I looked astern after the first hour it seemed as though we were still under the shadow of Saint Vincent. I knew later that we had made five miles. It was discouraging to look backwards, and I did very little of it in my runs afterwards. I would wait till the greyish blue of the island ahead had turned to blue and was shading into green and then I would look back to the island that I had just left and I would estimate that I was perhaps half way across the channel. Having assured myself that I really was half way across, l kept my eyes over the bow, noting the minute changes of the land ahead. But I am not yet half way across this channel.

Soon my eye began to focus on a persistent whitecap that my brain refused to believe was a sail. But the eye insisted and the brain had to give in when the speck refused to move -- it was always there, just to leeward of the Pitons -- and it grew into a definite shape. Its course must almost cross mine, for as it grew larger and larger, it edged to windward closing in on the Pitons and was at last directly on my course. Nearer it came till I could make out the figure of a man poised erect out over the water. Another second and I could see the line to which he was holding and which ran to the top of the mast. His feet were on the gunwale. Then I distinguished several forms aft of him in the canoe, all leaning far out to windward to see what strange bird the Yakaboo might be, coming up out of the south.

Native canoe under sail.

The news of my coming had not jumped the channel ahead of me, but these fellows had recognized my rig from afar as a rarity -- something to investigate. I shall never forget the picture of them rushing by. They might have been Caribs of old descending, like the Vikings that they were, on some island to be conquered. They came down the wind with terrific speed, the water foaming white under them, a third of the keel showing, the glistening forefoot leaving a train of drops like a porpoise clearing the water.

For an instant my eye held it ; the man poised over the sea ; the figures in the boat, bronze and ebony, tense with excitement ; the white, sun-bleached sails, now outlined against a blue sky and now thrown against an indigo sea, rivaling the brilliant snowy clouds above. As they shot by, close abeam, their arms shot up and they gave me a mighty yell while I waved my hat and shouted back at them. If this sight of a single canoe coming down the wind thrilled the hairs along my spine into an upright position, what would my feeling have been to see a whole fleet of them as in the old days? I would not look back -- I wanted the memory of that passing to remain as it was and I sailed on, thinking for some time of each detail as it was indelibly impressed upon my mind.

Like most of us, who are blessed with a lean body, I also have that blessing which usually goes with it -- an appetite which is entirely out of all proportion to the size of that lean body. Nervous energy as well as manual labor requires food and when I made my channel runs there was an expenditure of both -- and I needed feeding. I always had food handy in my cockpit.

My mainstay was the jelly coconut or water -- nut as they call it. This is the coconut that has not yet reached the stage where the meat is the hard, white substance which we meet in the kitchen pantry in the shredded form, but is still in the baby stage when the meat is soft and jelly-like. In this stage the milk is not so rich as later on, but is a sort of sweet coco-tasting water. I never wanted for a supply of coconuts.

The natives along shore invariably saw to it that there were four or five of them in my cockpit, prepared for instant use in the following manner : the native balances the nut on the palm of the left hand, while with a cutlass (not called machete in these islands that have not known the Spaniard, except as a pirate), he cuts through the hard, smooth surface of the husk and trims the pulpy mass, where the stem joins the nut, into a point. At any time, then, with a single slice of my knife, I could lop off this pulpy point and cut through the soft stem end of the inner shell, making a small hole through which I could drink the water.

When first it passes over your tongue, jaded by the civilized drinks which have a tang to them, your judgment will be, "Insipid!" Go out into the open and leave ice water a week behind you and your tongue will recover some of its pre-civilized sensitiveness. You will swear that there is nothing so cool nor delicious as the water of the jelly coconut. After the water has been drunk there is yet the jelly to be eaten. First a slice of the husk is cut oft to be used as a spoon. Then, using my knife as a wedge and my axe as a driver, I split open the nut and scooped out the jelly from the halves.

When my supply of pilot bread ran out I carried soda crackers and sometimes the unleavened bread of the natives. Raw peameal sausage helped out at times and there was, of course, the chocolate of which I have spoken before. I also carried other tropical fruits besides coconuts, mangoes, bananas, pineapples, but I never ate more than one sort on a run. The coconut was my mainstay, however, and that with a little bread and a piece of chocolate would make an excellent stop-gap till I could reach shore and cook a substantial evening meal.

I was now half way across the channel, I judged, for neither island had the advantage of nearness nor distance. After a while Vieux Fort began to work its way to windward of me and the canoe was still hanging bravely on to the Pitons. She was doing excellent work to windward, creeping up the long hollows in pilot's luffs as is the habit of this rudderless craft. The sum total of these small distances eaten to windward a little more than made up for what we lost when we lay-to for a combing sea. Saint Lucia had long since changed from a misty grey to blue grey, and then slowly the green of the vegetation began to assert itself in varying shades as patches of cultivation became defined. Dun-colored spots on the hillsides took the shapes of native huts. It was like the very slow development of a huge photographic plate.

When within a few miles of the island the wind began to draw to the south'ard, and as I eased the sheets of the canoe, she quickened her pace like a horse headed for home. The plate was developing rapidly -- I could make out the trees on the mountain ridges and the beaches along shore. Vieux Fort was on our beam, the Pitons towered over us ; then with the hum of tarred rigging in a gale, the centerboard of the Yakaboo crooned its parting song to the channel and we lost our motion in the glassy calm of Souffrière Bay. We had completed our first long jump.

High above me the projectile form of the Petit Piton tore an occasional wraith from the low-flying trade clouds. Inset in its steep side, some twenty feet above where I was now rowing, was a niched shrine to the Virgin Mary, to whom many a hasty prayer had been uttered during the fervor of bare deliverance from the rafales (squalls) of the channel, prayers probably quickly forgotten in these calm waters under the Pitons and the memory of them soon washed away in the little rum shops of the coast town, which gets its name from the Souffrière in the hills above it and gives that name to the bay before it. By this sign of the Virgin Mary, I was leaving for a time the Protestant faith of the outer Antilles and entering the Catholic. In a measure, I was leaving the English for the French, for although Saint Lucia has been in the possession of the English since 1803, there still remains the old creole atmosphere of the French régime.

As I swung around the base of the smaller Piton, the leveling rays of the late afternoon sun caught the distant walls of wooden houses weatherworn to a silky sheen. The dull red of a tiled roof here and there, the sharp white of what I soon learned were the police buildings, broke the drab monotone of the town. A little coasting steamer backed out, crab-like, from a cane-laden jetty and as we passed in the bay, three white cotton tufts from her whistle tooted my first welcome to Saint Lucia.

I had planned to show my papers to the police at Souffrière and then to pitch my tent on some sandy beach beyond a point that interested me just north of the town. I should then have a good start for my row along the lee coast on the next day and I should soon be channel running again -- to Martinique and the Empress Josephine -- I had an especial interest in her.

But one never knows. It happened at Carriacou and it is apt to happen at any time. The perverse imp, whatever his name may be, thrives on the upsetting of plans. I had no sooner crawled up on the jetty of Souffrière and stretched my legs when a black limb of the law confronted me.

"Dis no port ob entry," he said ; "you mus' go to Castries."Castries was sixteen miles farther along the coast and I had already traveled forty-two miles since sunup. I looked at my watch and the hands showed four-thirty. I looked out over the sea and saw the sun, like an impatient boy rushing through his chores, racing for his bath in the horizon, a huge molten drop, trickling down the inverted bowl of the firmament. If I now took to my canoe again and slept on the beach somewhere up the shore, I should get into trouble at Castries for I had already put my foot on shore.

I finally decided that it was two of one and half a dozen of another -- two being the trouble I should get into by staying here and six being the trouble I might get into in the proportionately larger town of Castries. Confound a government that spends thirty cents for red tape to wrap up a package worth ten!

Up to this time, my coming had not been detected, but with the increasing agitation of the policeman, it dawned upon the jetty stragglers that something unusual was on foot. Some one noticed the strange canoe tethered like a patient animal to one of the legs of the jetty. Some one else noticed that there was a strange person talking with the policeman. I was rapidly being discovered by a horde of babbling, ragged beach-loafers and fishermen, who followed like swarming bees as we made our way to the police buildings. The swarm was effectually barricaded outside as we entered the building, where I showed my papers to Sergeant Prout.

In these islands when precedent lacks, complexity arises. And here was something complex -- a man who traveled alone, voyaging in the daytime and sleeping at night on whatever beach he happened to land. The sergeant must needs have advice, so he sent for the leading merchant of the town and the lawyer. The merchant, being a man of business, said, "Ask your superior," and the lawyer, being a man of caution, said, "Place the responsibility on some one else," at which the sergeant telephoned to His Majesty's Treasurer at Castries. The reply I did not hear. My canoe was carried into the cobbled courtyard of the police buildings and my outfit was locked up in a cell next to that of a thief.

"And now," said I, "if you will lend me a coalpot and lock me up with my outfit I shall cook my supper and go to bed." Not a smile on the faces around me."But there is an hotel in thee town," came from a voice at my side, and not much higher than my belt, "I will conduc' you there."

He pronounced "hotel" with a lisp that made it more like "hostel," and called the article "thee." I looked down and beheld him who was to be my henchman during my stay in Souffrière. He was a little fellow, black as the record of a trust magnate and with a face that went with the name of Joseph Innocent.

I would take Sergeant Prout's word for anything and his nod in answer to my questioning look was a good voucher for Joseph. And so we walked out, Joseph parting the crowd before me, proudly carrying my camera and portfolio while I followed, a pace or two behind, to observe the quaint old town. Laid out in regular squares, the houses toed the line of the sidewalks in one continuous wall from street to street. For the most part, the walls were bare of paint, or if paint had ever been used, it had long since been crumbled by the sun and washed away by the rain. To relieve the dead geometric regularity, picturesque grilled balconies overhung the sidewalks, giving proof that at some time there had been life in the streets worth observing.

We passed the open square of the market with the bare, sun-heated church at the far end, facing the west, as though its memories lay forever behind it. Joseph stopped at one of the myriad doors in the walls of houses. Would I ever be able to find this door again? -- and I stepped from the street into the cool dark salle à manger of this West Indian hotel. The mulatresse, who received me, was of a better looking type, I thought, than the creole negress of the English islands. "Could I have food and room for the night?"

"Mais oui," for in spite of my shifty appearance my camera and portfolio were badges of respectability and vouched for me. I dispatched Joseph for some cigarettes and while awaiting his return I noticed that the mulatresse was setting places for two. I was to have company -- a comforting thought when I could not be alone on the beach. I am never so lonesome as when eating alone, where there are people about. On the beach I should have had the company of the setting sun, the tropical starlit night, and the murmur of the little rippling surf on the smooth sands -- but here! the shuffling of the silent negress as she placed the food before me would have been loneliness itself.

When Joseph came with the tin of cigarettes, I offered him a "thrupence," for he had served me well. But he was a diplomat from his wide-spreading toes to his apish face. There is a patois saying, "Zo quité yone boudé plein fait zo sote, " -- "Don't let a bellyful fool you."

"No! You give me de two copper," indicating the coins in my hand, "for you need de silver for other person." He was an artist, I learned later, and cared little for money -- but would I get him some paints and brushes when I reached Castries?

The mulatresse had scarcely announced, "Monsieur est servi," when the other guest entered. He was an Englishman -- of the island -- spare and well-groomed, as one generally finds them, a government engineer on his monthly tour inspecting the telephone system, which girdles the island. While we ate our thon (tuna) our conversation turned on the tuna fisheries of Martinique and I mentioned Josephine and Trois-Îlets.

"Josephine! Martinique! Why man alive! Josephine spent part of her childhood days right here in Souffrière and I don't know but what she was born on this island -- in the northern part -- at Morne Paix-Bouche."And so it happened that I was to be denied the beach to stumble upon a page or two of that life of contrasts -- pathetic and romantic -- of the Empress Josephine. Over our coffee and cigarettes my friend told me of Père Remaud of the parish of Gros-Islet in the north of Saint Lucia -- the man who knew more about Josephine's life in this island than any one else. I decided, then, to spend some time in Saint Lucia and I learned many things about her -- but who wants to read dry history sandwiched in between salty channel runs? Our conversation turned to other things and then died out even as the glow of our cigarettes. We were both tired and mutually glad to turn in.

The camera got them just as they had slipped through the high surf.

But the wakening effect of the coffee and the cold funereal sheets of the high antique four-poster onto which I had climbed to rest, kept off slumber for a while. What a cruise of contrasts it was -- from the primitive life of the Carib living on fish and cassava, I had sailed in a day from the fifteenth century into the eighteenth. From my roll of blankets on the high ground of Point Espagñol I had come to the more civilized, but not more comfortable, husk mattress of the French régime. I was not long in deciding that the husk mattress was no less aged than the four-poster. Perhaps the friends of Josephine had slept in this bed, on this very mattress -- whatever their sins may have been may this have shriven them! Sadness entered my mood and I fell asleep.

Can the lover of small indulgences begin the day better than I began my first morning in Saint Lucia? At six there was a knock at my door, followed by the entrance of the mulatresse bearing a huge basin of cold water with a calabash floating on its surface, the simplest and yet the most delightful bath I have known. Scarcely had I slipped on my clothes -- the mulatresse must have known by the sounds the progress of my toilet -- when another knock ushered in a small pot of steaming Liberian coffee such as only they of the French islands can grow and brew. There is but one sequence to this -- a cigarette. This, then, was my formula, after which I stepped out onto the street where Joseph was waiting for me.

Not far from the town, up in the hills, lies Ventine, the beauty spot of Saint Lucia. This is the safety valve, a sort of Hell's Half Acre, that saved Saint Lucia during the eruptions of Saint Vincent and Martinique. As the well-kept road wound upward, lined with orderly fields and occasional clumps of trees, I could easily imagine myself to be in southern Europe, for the morning was still cool and the road free except for an infrequent figure shuffling along at its ease with its burden balanced on top. It was pleasant to hear the prattle of Joseph with its French construction of the English and that soft inflection, which we lack so much in our own harsh language.

"Look! you see that bird there? Eet ees call the cuckoo mayoque by the creole. They say that God, w'en he was building the world (but I don' beleeve it), ask the cuckoo to carry stone to the stream. But the cuckoo would not do it because it would soil his beautiful fethaire. Then God say, 'For that you shall never, drink from the stream an eef you do you will drown. An' now the cuckoo can only get water from the flowers and leaves."A little farther on, he darted to the side of the road and brought back a leaf of the silver fern. He told me to hold out my hand -- "no, wiz zee back upwards." Placing the leaf on the brown skin he gave it a slap and the leaf slipped off leaving the delicate tracery of its form in a silver powder. And so it was on that delightful walk, I came to like the little native, bright and full of spirit. Some day he may, as a regular duty, open my door in the morning and say, "Will you have your, coffee now, sir, or w'en you arize?"

We finally arrived at the Ventine, which is the thin-crusted floor of an ancient crater. The sulphur smell that greeted me brought back memories of Yellowstone Park. From Southern Europe I had been whisked back to the States. And to carry the illusion still further I found there three Americans, Foster, Green and Smith (good plain Yankee names of no pretension), who were working the sulphur of the crater. We fell on each other's necks, so to speak.

One needed a guide and Foster took me about on the hot floor to see the boiling mud pools and the steam jets. On our way up to the cottage where the men lived with their families Foster showed me the natural advantages of living in a place like this. The region of the Ventine would be a wonderful place of retirement for the rheumatic cripple. Here were hot springs of temperatures from tepid to boiling, cold mountain streams that made natural shower baths, as they tumbled down the rocks, and pools of curative mineral water.

As we walked along the path Foster dug his hands into the bank. "When you want to wash your hands just reach into the side of the hill -- here -- and haul out a lump of this soft clay stuff. Rub your hands together and a little farther on -- here -- you have the choice of either hot or cold water to wash it off in. You see, my hands are as soft as a baby's skin."

He talked like an advertisement. They are planning to build a hotel at the Ventine some day. If they do it will be a new Souffrière come to life and I can imagine no more delightful resort.

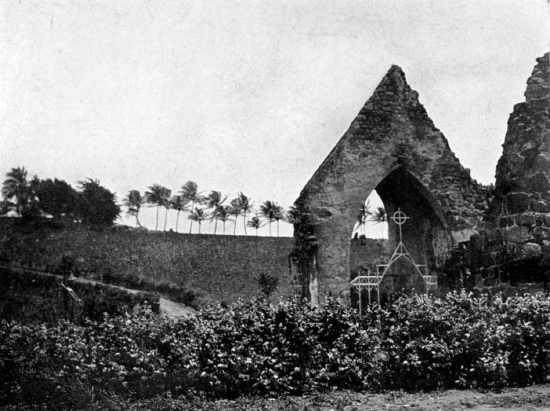

We left the Ventine in the cool of the afternoon and passing the town walked out along the broad east road to the ruins of the old French baths, where the aristocracy of France, some of them exiles, and some come to the island to recoup their fortunes, were wont to take the cure. There is but little now remaining, a few walls, a tank into which the sulphur water flows from the mountain stream, and a massive stone arch set in a thick woods that takes two hours from each end of the day and holds a gloom like a shroud for the dead past. A cow was grazing where grace once trod and where perhaps the little Yeyette* came with her elders. That evening I chatted with a man, Monsieur Devaux, whose grandaunt, Mademoiselle Petit L'Étang, had often spoken of having played with the little Josephine, at the estate of Malmaison in the hills to the north of Souffrière.

But there was little else to be learned and the next morning I left for Castries.

Offshore, trying to claw into the wind against the tide, was a little sloop which somehow looked familiar. It was calm alongshore and I rowed for an hour. Then a breeze came directly from the north and I made sail for beating. As I neared the sloop on the out tack she ran up a signal. I dropped my mainsail for an instant to let them know that I understood, and ran in again on the other tack. She was the Glen Nevis from Grenada and had called at Kingstown on her way to Saint Lucia with ice.

When she followed me into port an hour later, I found that my Man Friday of St. George's was in command.

* Childhood name of the Empress Josephine.

They had left Kingstown the day before I had left Château Belaire, and although I had stopped off a day at Souffrière, I beat them into Castries by an hour. In other words, it had taken them seventy-two hours to cover the sixty miles from Kingstown to Castries. My time for traveling the same distance was twenty hours. This showed the advantage of the canoe as a vehicle in these waters, for I could not only sail the rough channels but also slip along under the lee of the islands where the larger boats would be helplessly becalmed. As these fellows sail they must, of necessity, lose valuable ground to windward by dropping away from the island they are leaving to avoid calms and then they must beat their way up to the next island.

Compared with Grenada and Saint Vincent, the lee coast of Saint Lucia is low and uninteresting except for two wonderful harbors, close together, near the northern end ; Cul-de-Sac, the location of the Usine Central for the manufacture of sugar, and Castries, the coaling station of the English islands, with its Vigie, the lately abandoned Gibraltar of the British West Indies.* It was in the hills between these almost landlocked harbors that Sir John Moore fought with the French and the Caribs and learned the real art of warfare that made possible his marvellous retreat at Coruña.

As we approached Castries, a large, white yacht came up from over the horizon and slipped into the harbor. She proved to be the Atinah -- belonging to Edouard Rothschild and flying the French flag. She had bumped on a reef south of Cuba and came here to coal before going home to dock. A Norwegian tramp, probably owned by an American company, stole around the south of the island and came up behind me, a huge mass of ocean-going utility, and swung into port after the yacht.

* Shortly after the outbreak of the present war in Europe

the Vigie was fortified with guns brought over from Martinique

and garrisoned in 1915 by a company of Canadian soldiers.

An Englishman came out, relieved of coals she had brought from Cardiff, her rusty sides high out of water, the tips of her propeller making a white haystack under her counter. The little coasting steamer, which had saluted me two days before, bustled out of her home on her daily run to Vieux Fort.

There was commerce in this port -- I had not been near a steamer for two months. Before sailing into the harbor, we made an inquisitive tack offshore in order to have a peep at Martinique. There she lay -- a little to the westward of Saint Lucia ; the arc was swinging back and I should soon be in the Leeward islands. Distinct against the haze of Martinique stood the famous Diamond Rock and here, only six miles off, lay Pigeon Island, lifting its head, a lion couchant with Fort Rodney in its mane.

On the other tack we ran into the busy harbor. French, English, and Norwegian flags were there. My little ensign, no larger than a bandana handkerchief, was all that represented the United States in this large company. But the Yakaboo flitted past her overgrown children -- for after all the canoe is the mother of them all -- to a quiet corner that showed no change since the advent of steam.

I had decided to spend some time in Castries -- looking into the past of a certain lady. I ought to make the type appear shamefaced as I write this, but you already know who the lady is, or was, and that she has been dead nearly a century and her past was a romance. There comes an indefinable sense of peace and quiet when one sails into a secure and almost landlocked harbor such as the carénage of Castries, but I did not know that I was only sailing from the vicissitudes of the Caribbean to the uncertainties of a veritable sea of hearsay concerning Josephine.

For instance, there was an old negro who had seen the Empress in Castries when a little child. Whether he was the little child, or she was the little child, I do not know -- perhaps it was Castries that was the little child. He was brought to me one day as I stood in the street chatting with one of the merchants of the town.

"Undoubtedly old," I said to my friend, as one would comment upon a piece of furniture. He seemed a youth compared with some of our old Southern darkies, shriveled and cotton-tufted.

"Quel âge?' I yelled at him, for he was somewhat deaf."Cent onze e' sep' s'mains," came the answer. One hundred and eleven years and seven weeks! If I had not caught him unawares he might have given the days and hours.

But his age was not so remarkable as his memory. He remembered having seen Josephine on the streets and especially at the time when she left Saint Lucia for Martinique on her way to France to marry Beauharnais. There was no doubting that honest old face and there was nothing but admiration for a memory that reached back not only to youth and childhood, but even to prenatal existence. He was born two years after Josephine had paid her last visit to these islands! I took his photograph and paid him a shilling, which shows that a wonderful memory is nothing if not a commercial asset.

My papers from St. George's, which had been viséd from port to port would serve me no longer since I was now leaving for Martinique, which was French. One morning I walked into the office of the French consul, who, it seemed to me, was suspiciously suave and gracious. The idea of traveling about in a boat of less than a quarter of a ton was very amusing. He filled in the blanks of an impressive document, which I stuck in my pocket. When I asked the amount of the fee he said, "Twenty francs." "Whew!" I muttered to myself, "no wonder he was so blasted polite."

Out past the Vigie and I was happy again. One is always glad to run into port, but the voyager is doubly glad to leave it again. There are countless petty annoyances on shore that one never meets on the broad seas. I often worry about the weather, but most of that worry is done when I am ashore. As soon as I stepped into the canoe that morning I felt that I was leaving my small troubles on the stone quay, whimpering like a pack of forlorn dogs. I should lose sight of them and the quay as soon as I rounded the Vigie.

After sailing through two rain squalls and making an investigating tack under Pigeon Island, I headed for the beach of the village of Gros-Islet, for I had business there. I wanted to see Père Remaud and examine some of the parish signatures. As I beached the canoe, Henry Belmar, a fine young colonial Englishman, came through the crowd of natives to meet me. He was riding through Gros-Islet on governmental duties, had seen me in the bay, and had ordered food at one of the houses in the town. The thoughtful hospitality of the colonial Englishman has often made me think upon the manner in which we too often treat the stranger who comes to our shores. If he is outré, we lionize him and the women make a freak of him. If he is of our own kind, we let him shift for himself. We drank our febrifuge with the usual "chin-chin," and after luncheon set out for the house of Père Remaud.

The priest was a young man, full of strength and vigor, much, I thought, as Père Labat would have been had we known him in our age. Père Remaud was interested in the things of the world. He lived for his parish, read, shot ramiers (pigeons), and could talk intimately on the politics of my own country. While I had been eating with Belmar, the priest had been down to the beach to see my canoe and at the moment when we arrived he was hastily turning the leaves of a French sporting catalogue to see whether he might discover to just what species the Yakaboo belonged -- much as he would attempt to classify a strange flower which he had found in the hills of his parish.

I spent the afternoon with him, looking over the old parish records. But for the faded paper on which they stood out in bold lines, the letters and signatures might have been written yesterday. There was the signature of Louis Raphael Martin, a planter of Saint Lucia, who had known Josephine here and had been received by her at Malmaison in France. There was that of Auguste Hosten under the date of 1810, who, Frédéric Masson says, loaned a large sum of money to Josephine at the time of the Revolution, when the guillotine had taken her first husband and before she met Napoleon.

We talked, and I made many notes during the long afternoon till at last the yellow sunshine gave warning that I must leave. Père Remaud came down to the beach with me and as we heeled to the evening breeze I heard his last "Bon voyage" above the babble of the natives.

The same puff that carried the last adieux of Père Remaud helped us across the white sandy floor of the bay and left us, close to the shores of Pigeon Island. Three whaleboats were lying on the beach and as I stepped ashore their crews came straggling down to meet me. I found that the man in command of the station was Napoleon Olivier of Bequia, a brother of José at Caille, and I was again in my whaling days of the Grenadines. I was soon as far from Josephine and Père Remaud as the twentieth century is from the eighteenth -- but not for long. Accompanied by the two sons of Olivier, I climbed to the famous old fort, now called "Rodney," where that admiral, second only to Nelson, watched for the French fleet to come out of their hiding in the bay of Fort Royal (now Fort de France), thirty miles to the north, in Martinique. His own fleet lay below him in the Saint Croix roads, like impatient hounds tugging at their leashes, eager to be in chase of their quarry.

The French at last slipped out on the night of April 8th, 1782, the news of their departure being signaled to Rodney by means of a chain of English lookout ships. Rodney was immediately on their heels and on the 12th met the French in the Dominica channel, where he fought the battle of "The Saints."

The fort itself is scarcely more than a rampart with a powder magazine on the east side and a flagstaff stepping in the center. There were no guns left and the trees, growing out of the pavement, told of long years of disuse. The sun had dropped below the ridge of the island as we scrambled down again through long rank grass, waist-high, and through a small dark grove of trees, among which there were several tombs of officers, their inscriptions still decipherable, the last narrow earthly homes of men who had died while stationed here, not from the bullets of the French, but from the insidious attack of that enemy which they knew not -- the mosquito.

I cooked my supper with the whalemen in the ruins of the old barracks. A rain tank, still intact from the time of the occupation, furnished water and I was soon yarning with Olivier over the bubbling pots. The season had been a bad one, only one small whale had been caught. One of the best harpooners was lying sick with fever in Gros-Islet, and the whole outfit was in a state of black dejection.

Poor Olivier! He was not only doomed to lose his harpooner, for three years later when I sailed my schooner into the quiet haven of Bequia he came aboard and, sitting on the top step of the companionway, he told me with tears in his eyes that one of his sons, who had taken me up to the fort, had died of fever shortly after I had left Pigeon Island. He had no photograph to remember his son by, but he remembered that I had taken a snapshot on the rampart -- would I give him a print?

Supper over, we put up impromptu tents in the long, soft grass above the beach where the boats lay, for the ruins, they said, were full of fleas. It may have been fleas or it may have been superstition that inhabited the barracks with jumbies. The tents were impromptu, old sloop sails thrown over the masts of the whaleboats. One end of the masts rested on the ground while the other was supported by crossed oars lashed together about seven feet above ground. Had these shelters not been put up after sunset and taken down before sunrise I might have had an interesting photograph of shipwrecked mariners. I crawled in with Olivier, for it would save me the work of pitching my own tent. I was awakened by the chilly drizzle of a morning squall.

As I got up and shook myself at sunrise -- that is 5 :51 on that particular day -- (the sun did not rise for us until sometime later, when he edged above the Morne du Cap on Saint Lucia), the weather did not look promising. Had it been the fifth day of the first quarter I would not have started for Martinique, but it was the fifth of the second, which had shown a lamb-like disposition, and there were two days of it left -- I was on the safe side. The indications were for rain rather than wind and I decided to take the chance. Olivier was a bit doubtful.

I cooked my breakfast with the men in the barracks, dragged my canoe down to the water's edge and watched the weather. At eight o'clock, the rain having ceased, I bade good-bye to the whalers, who had decided not to try for humpbacks that day, and was off. As we sailed out through the reefs by Burgot Rocks the heavy surf gave warning that there would be plenty of wind outside. Once clear of Saint Lucia I laid my course for Diamond Rock, a good six points off the wind.

What a comfort it was to ease my sheets a bit and to know that if the current began to take me to leeward I could make it up by working closer to windward. Those extra points were like a separate bank account laid up for a rainy day.

The canoe enjoyed this work. She fairly flew, sliding into the deep troughs and climbing the tall seas in long diagonals. In half an hour Saint Lucia behind me was completely hidden by rain clouds and so was Martinique ahead. The two islands seemed to have wrapped themselves in their vaporous blankets in high dudgeon, like a couple of Indian bucks who have failed to wheedle whisky out of a passing tourist. Fearful lest the weather might break and come up from the southwest, I kept a constant watch on the procession of the trade clouds in the northeast, ready to come about with the first weakening of the wind.

Afraid? not exactly -- but cautious. The Yakaboo drove on like the sturdy little animal that she was. We flow knew each other so well that we did not even bother to head into the breaking seas, except the very large ones. Some of them we could roll under and slip by. Others came aboard and at times I was waist deep in water and foam, sitting on the deck to windward, my feet braced in the cockpit under the opposite coaming. If there had not been the danger of filling her sails with water, I could have made the mainsheet fast for she practically sailed herself. Between deluges, I bailed out the cockpit with a calabash.

Once in a while she would hang her head and then I hove-to to bail out the forward compartment with a sponge. The exhilaration of the Saint Vincent channel was nothing compared to this. The water was warm and my constant ducking was not unpleasant. I thought I could feel a tingle in the region of my pre-evolute gills.

The ruins of the church at Owia. The bell and the ladder can be seen at left.

It may seem strange that in these channel runs where the trade blew strong, the force of the wind never seemed to bother the canoe. Although it was usually blowing fully twenty miles an hour and often twenty-five, I was obliged to reef my sails but four times on the whole cruise ; on the run to Dominica, when the wind was very strong ; again, under the lee of Dominica ; in the run to Guadeloupe, when the canoe was going too fast in a following sea, and, for the same reason, on my run to Saba. I have often carried full sail when a large sloop has been obliged to reef.

The reason for this is that the wind close to the surface of water, broken up into ridges from three to eight feet in height, is considerably retarded and the stratum through which the low rig of the Yakaboo moved was not traveling at a rate of more than three-fourths the actual velocity of the free wind. Upon approaching land, where the seas began to diminish in size and before I had reached the influence of the down draft from the mountains, I could always feel a slight but definite increase in the force of the wind.

Sailing as I did -- seated only a few inches above the water -- I had an excellent Opportunity to observe the flying fish which rose almost continually from under the bow of the canoe. Although they were smaller than those I have seen in the channels off the California coast -- they were seldom more than about nine inches long -- their flight did not seem to be appreciably shorter. Their speed in the water immediately before they emerge must be terrific for they come out as though shot from a submarine catapult ; their gossamer wings, vibrating from the translated motion of the powerful tail, make the deception of flight most real.

The flight is in effect the act of soaring with the body at an angle of from ten to fifteen degrees with the horizontal. The wings are close to the head and the lower part of the body often passes through the crest of a wave from time to time when the tail seems to give an impetus to the decreasing speed of the flight. This, however, may be an illusion, due to the dropping away of the wave, which might thus give the fish the appearance of rising up from the water. I have spent many hours watching these singular fish and, while there can be no doubt that they do not actually fly, it seems almost incredible that a fish can hurl itself from the Water with sufficient force to rise to a height of twenty or more feet and soar for a distance of from three to four hundred feet -- perhaps farther.

The land ahead had shaken off its cloud blanket and was now rapidly defining itself, for this channel was shorter than the last one and my old enemy, the lee tide, had been scarcely perceptible. As I held the canoe up for "Diamond Rock," I again noticed the decided veering of the wind to the south'ard, and from time to time I had to ease off my sheets till the canoe was running well off in a beam sea that moderated as I approached land. The sky, which had been well clouded during most of the run, opened at a fortunate moment while I hove-to, stood up in the cockpit, and took a photograph of the famous Rock. There was no hope of landing in that run of sea and I had to be content with a hasty survey of the Rock as the canoe bobbed up and down, her nose into the wind.

Were I writing this narrative true to events, I should have no time to describe the Rock and relate a bit of its history for I had scarcely time to stow my camera when a squall came chasing down on my heels. I hastily raised the mainsail and ran "brad aft," as the harpooner Bynoe would say, to get plenty of sea room. When the squall did catch us, we hove-to with the jib safely stowed and the mainsail securely lashed so that the wind could not get its fingers into it, and with the sturdy little mizzen dutifully holding the canoe into the wind.

You shall have the story now while I am sitting in the cockpit -- doing nothing but watch the Rock disappear in the mist to windward, while the Yakaboo is backing off gracefully at a rate of four miles an hour.

Diamond Rock rises in the shape of a dome to a height of five hundred and seventy feet, a mile distant from the Martinique shore. In 1804, when the English and French were making their last fight for the supremacy of the Caribbean, Admiral Hood laid the H. M. S. Centaur close under the lee of the Rock, put kedges out to sea, and ran lines to the shore. Fortunately, calm weather aided the Admiral in his operations and he was able to hoist three long 24s and two 18s to the top of the Rock where hasty fortifications were built. Here Lieutenant Maurice, with one hundred and twenty men, harassed the French fleet.

The Rock was named H. M. S. Diamond Rock and for sixteen months this stationary man-of-war held out against the French, who had two 74s, a corvette, a schooner, and eleven gunboats. Lack of food finally caused these gallant men to surrender and so great was the admiration of the French governor, the Marquise de Bouillé, that he treated them as his guests at Fort Royal (Fort de France), till the proper exchanges could be made. By a strange coincidence, this same Maurice, who had become a captain, in 1811 captured the island of Anholt and successfully held it against the Danes.

While I have been yarning to you about Diamond Rock, I have also partaken of my frugal sea-luncheon of coconut, pilot bread, and chocolate. I believe, just to make up for the nastiness of the weather, I raided my larder under the cockpit floor to the extent of a small can of potted meat, and I remember saving the empty tin till I was well in shore, for I did not care to excite the curiosity of a chance shark that might be passing by.

The squall was a mixture of wind and spiteful rain and I thought of the Yakaboo as akin to the chimney sweep's donkey in "Water Babies." For an hour it blew hard and then let up as quickly as it had come, the sea subsiding as if by magic. I found that we were well oft shore nearly due west of Cape Solomon, four miles from the point where the squall had picked me up. Shaping our course past the cape, we soon ran into the calm of the picturesque bay of Fort de France.

Tucked well back from the sea, on the northern shore of the bay, lay the capital of the island. The afternoon was in its decline and the level rays of the sun striking into the low rain clouds that hung over the land threw a golden light on the town and hills, making it a yellow-skied picture by an old Dutch master. The effect of days gone by was heightened by the presence of a large square-rigger that lay in the anchorage with her sails brailed up to dry after the rain. No steamer was there to mar the illusion -- the picture was not modern.

As I rowed closer to the town I turned from time to time to see what changes were going on behind my back. On a bluff close aboard were the pretty homes of a villa quarter and over one the tricolor of France proclaimed the governor's house. Beyond was a row of warehouses fronting the sea and beyond these, as though behind a bulwark, rose the cathedral steeple. At the far end of the row of warehouses a long landing jetty ran out at right angles to the water front. Still farther to the eastward Fort St. Louis lay out into the harbor jealously guarding the carénage behind it. At the water's edge and not far from the shore end of the jetty was a building with the revenue flag over it and for this I shaped my course.

As I neared the government landing the harbormaster's boat came out with its dusky crew of douanes (customs officers), wearing blue and white-banded jerseys and the French helmet of the tropics, with its brim drooped in back to protect the nape of the neck. I passed my papers to them and started to follow. The man in the stern, who now held my expensive bill of health, waved me back.

"Jettez votre ancre!"I answered that I carried no anchor and they pulled away as from a pest.

"Restez la!" he yelled, pointing indefinitely out into the middle of the bay. The crew landed their officer and then rowed out again, placing themselves between me and the shore. Half an hour passed ; I could see the people of the town trickle down through the streets and gather along the water front. Then I began to notice that there was something wrong with the Yakaboo. She was tired and woman-like she gave way -- not to tears, but the reverse. She leaked. She had had a hard day of it and wanted to sit down somewhere ; the bottom of the harbor being the nearest place, she started for that. A seam must have opened on the run across and I had to bail.

But what on earth were those fellows doing with my bill of health and why on earth did they not allow me to come ashore? Between spells of bailing I took up my oars and started to circumnavigate the douanes, but they were inshore of me and had the advantage. The sun sank lower and the crowd along shore became denser. Finally it dawned upon me. My expensive bill of health was dated the day before and the customs officers were trying to guess what I had been doing the day before and where I had been the previous night. Why they did not ask me directly I do not know, and what they actually thought and said to each other I never heard. That they took me for some sort of spy I am certain.

Two weeks in quarantine began to loom up as a vivid possibility. I then remembered that "Monty" at Kingstown had given me a letter to his brother-in-law, a merchant by the name of Richaud, who lived in Fort de France. The next move was to get the letter to Richaud -- he might be standing in that crowd on the jetty. So I took the letter out of my portfolio and put it in my pocket where it would be handy. Then I gave the Yakaboo a final sponge-out and started to pull at a smart pace away from the jetty. The crew in the harbormaster's boat swallowed the bait and quickly headed me off.

In a flash I yanked the canoe about and rowed for the jetty, under full steam, at the same time yelling over my shoulder for Monsieur Richaud. Luck was with me. There was a movement in the crowd and a little man was pushed to the outer edge like the stone out of a prune. In a jiffy I was alongside and the letter was in his hands. The baffled douanes, who had turned by this time and were after me full tilt, nosed me away from the jetty, while I lay oft, softly whistling "Yankee Doodle." This seemed to take with the crowd and they applauded. They were not in sympathy with douanes -- few West Indians are, for they are all fond of smuggling.

Whether it was Monty's letter backed by the pull of Monsieur Richaud, who seemed to be a man of some importance, or whether the officials decided to call it a day and to go home, I don't know, but I was at last beckoned to come ashore and just in time, for the Yakaboo sank with a gurgle of relief in the soft ooze on the beach. Before I knew what was going on, my whole outfit was bundled into the customs office to undergo the inspection of the officials. Even the canoe was bailed out and carried into the barracks, where she rested on the floor by the side of a gunrack filled with cumbersome St. Étienne rifles. There being no Bible handy I placed my hand on the next most holy thing, the bosom of my shirt, and swore that after this I would cruise in seas more homogeneous as to the nationality of their islands. While this silent ceremony was going on, the douanes looked at me in an awed way and one of them muttered "Fou" (crazy). He was probably right.

But Monsieur Richaud was there and he introduced himself to me. He had been expecting me for some time, he said, and I explained as best I could -- it was mental agony to try to recall from a musty memory words that I had not used for ten years or more -- that I had spent some time with the Caribs in Saint Vincent and some time in Saint Lucia, since I had left "Monty." Monsieur was a little, jolly round-faced Frenchman with the prosperous air of a business man of some consequence. He was reputed to be one of the rich men of Fort de France. Would I bestow upon him the honor of dining with him at his house? I would bestow that honor. We said "au revoir" to the douanes and stepped out into the street.

CHAPTER VIII.

MARTINIQUE -- FORT DE FRANCE.

IT WAS DARK and it was raining. My clothes were already wet and I sloshed along the narrow sidewalks behind the little man like a dripping Newfoundland dog. His wife was ill, he said, but he wished to at least give me a dinner, a change of clothes and then find me a lodging place. I had become so used to wet clothing that I forgot to bring my dry duds. I could see little of the town as we walked along the dark streets, but the impression was that of a small city -- larger than any I had yet seen in these islands. At our elbows was a monotonous unbroken wall of house fronts with closed doors and jalousied windows, which occasionally gave a faint gleam of light. Presently my friend stopped in front of one of the doors and pushed it in. We stepped into a sort of wide corridor at the farther end of which was another door through which we passed into my friend's house. The house in reality had two fronts, one on the street and this which faced on a sort of patio which separated it from the kitchen and servants' quarters. I made this hasty survey as the master gave some orders in patois to a large negress, whose attention was fixed on my bedraggled figure, which gave the impression of having but lately been fished out of the sea.

First of all there was that enjoyable little liquid ceremony, "a votre santé," in which I rose in the estimation of mine host upon denying allegiance to "wisky soda." This should be further proof that I was no English spy at least. Then I was led upstairs to the guest room which Monsieur was now occupying. Monsieur was short and beamy, while my build was of the reverse order, and the result of the change of dry clothes which I put on was ludicrous -- but I was dry and comfortable, which was the main thing. It was pleasant to know that I could now sit down in a comfortable chair without leaving a lasting salt stain behind me, pink-dyed from the color which was continually running from the lining of my coat. What little dignity to which I may lay claim, took wing at the sight of a foot of brown paw and forearm dangling from the sleeve of the coat. In like manner the trousers withdrew to a discreet distance from my feet and hung in desperate puckers around my middle.

Thus arrayed I was ushered into the presence of Madame Richaud, who lay recovering from an attack of fever in an immense four-poster. I paid my respects, assured her of the good health and well-being of her brother, and bowing with as much grace as possible, I followed my host to the drawing room.

The door through which we had passed from the street to the house of Monsieur Richaud was what one might call a general utility door, used by the master of the house on all ordinary occasions and by the servants and tradespeople. This door, as I have said, opened into a sort of corridor or antechamber through which one had to pass before gaining access to the house proper. There was, however, another street door, which opened from the sidewalk directly into the parlor or living room, where I now sat with my friend. This gives an uncomfortable feeling of intimacy with the street -- in a step one moves from the living room to the sidewalk. It made me think of one of the smaller canals of Venice, where I had seen an urchin dive from a front window into the street. On either side of this door were two windows, lacking glass, with jalousies between the interstices of which I could now and then see the whites of peeking eyes.

It is in the nature of these people to be fond of street life and during my stay in Fort de France I noticed that the little balconies, with long French windows opening upon them, which projected from the second stories, were occupied most of the time. The aspect of the glaring white and yellow houses, monotonous as the sheer walls of the Wallibu Dry River, could never be so pleasing as the green courtyards in the rear, viewed from large airy galleries. It was just the drift of the street, a casual word now and then and a few exchanges with neighbors similarly occupied.

As we talked, the thought came to me that there was at least one advantage to this parlor street door -- it was handy for funerals. Strange to say, I saw such a room put to just this use the very next day. The corpse was laid in state in the parlor and the doors were wide open so that any one, who wished, might enter in and look. There is, of course, some degree of common sense in this, for the rest of the house being practically cut off, the family need not be disturbed by the entrance of numerous friends, some of whom may not alone be satisfied in viewing the corpse, but take a morbid delight in viewing the grief of others.

But mall this had little to do with the dinner which was announced from the door of the adjoining dining room. Monsieur Richaud's two children, a boy and a girl in that nondescript age which precedes the bachfisch, now put in their appearance, the girl proudly taking the place of her mother at the head of the table. The dinner was excellent, but what I ate I did not remember even long enough to write in my note-book the next day, for while I was mechanically eating a soup that was delicious, I could give no specific thought to it, but must concentrate my entire attention to fetching up those few French words which were resting in the misty depths of my mind as in the muddy bottom of a well. Having "dove up" those words, I used them in a conversation which, while it was understood by Monsieur Richaud, afforded considerable amusement to the children. But the little Frenchman fared no better. Wishing to impress me with his familiarity with the English language he described the beauties of the northern coast of Martinique. He came to a fitting climax when he told of a river -- "w'ich arrive at zee sea by casharettes."

When the substantial part of the meal was over, a wash basin, soap and towel were passed around -- satisfactory if not aesthetic -- the three articles reminding me of their relations on the back stoop of a western farmhouse. After this, the fruit, which in this case was mango. I will not repeat the ponderous witticism regarding the mango and the bathtub. I have often speculated on this joke, however, and have almost come to the conclusion that it was invented first and the fruit discovered afterward. I can imagine Captain Cook suddenly starting up and slapping his thigh. "What ho!" he shouts, "I have thought up a most excellent joke, but I must find a fruit to fit it." And so he sets forth, discovers the mango and circumnavigates the globe.

However, we ate mangoes and our fingers became messy. As I was looking for some place to rest my hands where they would do the least damage to table linen, the negress, who had been serving us, brought in four plates with large finger bowls on them. There was tepid water in the bowls and by their sides were small beakers about the size of bird-baths. First we took up the beakers, filled them with water from the bowls and set them aside. Then we washed our finger tips in the bowls and finally dipped them in the clean water in the beakers and wiped our lips, an aesthetic proceeding which averaged the use of the wash basin and the soap. This rite concluded, the beaker was upset in the bowl -- a signal that the dinner was over.

Thus dried, fed and doubly cleansed, my sum of content lacked only tobacco and a bed. They raise their own tobacco in Martinique -- Tabac de Martinique -- and that it is pure is where praise halts and turns her back. As for strength -- I called it Tabac de Diable. I have shaved the festive plug and smoked the black twist that resembled a smoked herring from the time of the Salem witches, but these are as corn silk to the Tabac de Martinique. I had finished my supply of tobacco from home and now, forced to use the weed of Martinique, I "learned to love it." There was nothing else to do. It reminded me of the tenderfoot who leaned up against a white pine bar in the Far West and asked for a mint julep -- "Well frappéd." As the barkeeper produced a tumbler and a bottle he said, "You'll have three fingers of this bug juice and YOU'LL LOVE IT."

But the Tabac de Diable served me a good turn. Half a year later, in the cozy tap room of the Fitzwilliam Tavern, I incautiously left a partly smoked cigar within the reach of a practical joker, who, taking advantage of my preoccupation in a book, watched the cigar go out and then with the aid of a pin inserted a piece of elastic band into the end of the cigar. I did not notice the anticipation of a bit of fun on the faces of the men who had come from an uninteresting game of bridge in another room. I relit the cigar and resumed the smoking of it, still deeply engrossed in my book. I remembered later that one by one the jokers had left the room with silent tread as if in the presence of the dead. For once I was alone in the room and I had the fireplace to myself. I finished the cigar and threw the stump into the fire. It was the Tabac de Diable that had inoculated me and for some time after I left Martinique I found that I could smoke almost anything that was at all porous and would burn if an indraft was applied to it. But I did not enjoy it that first time when Monsieur Richaud handed me a Martinique cigar.

There now remained the last want -- a bed -- and my friend guessed this for I nearly fell asleep over his cigar.

He led me out into the deserted streets lighted by a faint starlight and still shining from the rain which had let up. We turned into one of the main thoroughfares at the end of which blazed an electric light, yellow, like the moon rising through a mist. Here flourished the "Grand Hôtel de l'Eurôpe," a name, I believe, as legion as Smith. I fully expect, after crossing my last channel, the Styx, to find a sign on the other shore thus -- "Grand Hôtel de l'Eurôpe -- Coolest Spot in Hades -- Asbestos Linen -- Sight Seeing Auto Hell/speed leaves at 10 A.M. -- Choice New Consignment of Magnates seen at Hard Labor."

My tired senses made scant note of the marble-floored room, the click of the billiard balls, and the questioning glances of the wasp-betrousered French officers, and I bade good night to my host, who had vouched for my harmlessness and left me in charge of the clerk.

The kaleidoscope day came to an end as I crawled under the mosquito bar of an immense four-poster, in a room on the premièr étage, and dove between the sheets with a grunt of satisfaction.

At first I thought it was the love song of a mosquito, but as I began to awaken the sound resolved itself into the thin blare of a trumpet-call and I wondered where I was. My eyes, directed at the ceiling when I opened them, caught the rays of the morning sun, sifted through the jalousies and striking the gauze canopy over me in bands of moted light. The trumpet sounded again -- this time almost under my window -- and stretching out of bed like a snail from its shell, I peeked through the vanes of the jalousie and saw a company of soldiers returning from their morning drill. There was a delicious novelty about it all that made me feel absolutely carefree, and, as I thought of the Yakaboo and her precious outfit, I hoped that they, as well as I, had rested in the customs station with its antiquated St. Étienne rifles for company. I hoped that there had been no quarrel between my Austrian gun and the Frenchmen and that my little British rifle had not flaunted the Union Jack in their faces. I was in that coma of carelessness when if an earthquake had come to crush out my life with the falling of the ponderous walls about me, I would have reproved it with the dying words, "Oh, pshaw, why didn't you wait till I had finished my cruise?" This feeling is worth traveling to the ends of the earth to experience.

A knock on the door brought forth a hasty "Entrez" as I slid back between the sheets. An aged negress brought in a small pot of coffee and a pitcher of hot milk which I found to my horror would have to stay my hunger until the hour of déjeuner at eleven.

Later, another knock ushered in my clothes from Monsieur Richaud, already washed and dried. My precious shirt looked like a miserable piece of bunting after a rainy Fourth of July, faded and color-run. I dressed and sallied forth to investigate the town.

Fort de France was as new and strange to me as St. George's had been and far more interesting. An impending week of rainy weather decided for me and I made up my mind to spend that week here. Until I was ready to put to sea again and sail for Dominica I could not take my outfit away from the customs office. Camping along shore, then, was out of the question. There was no alternative for me than to become for the time a part of the life of the town. Curiously enough, I find that one passes through various phases during the first few days in a new town or country. At first there is the novelty of the place which appeals to one. This is followed by a period of restlessness -- the first blush of novelty has worn off and one comes almost to the point of hating the place. It is like the European tourist who rushes upon a town, gorges himself with what pictures and sights are easily accessible and then in a fit of surfeit hates the thought of the rich optical food before him. But then comes the third stage, which lasts indefinitely, when the spirit of the town makes itself felt and one begins to see through the thin veneer of first impressions and to make friends. Those first impressions -- unless they are very striking -- vanish little by little till one comes to regard the place more or less with the eyes of the native. After all, this whole process is both natural and human. It is during the last stage (granting always that the town or country has any interest for one at all) that the residence in all out of the way places is brought about of stray Englishmen, Scotchmen, Irishmen and in more recent years Americans. One commonly hears the admission, "I didn't care for the place at all at first but somehow I became fond of it and here I am -- let's see, it's blank years now."

My first care was for my outfit which I was allowed to overhaul and put in order in the barracks room. My portfolio and camera I could take with me to the hotel, but the latter was of no use for my films became fogged from the excessive moisture of a rainy week and when I did try to make an exposure it was only of some conventional subject. I could not wander at random from the confines of the town nor edge near the picturesque carénage in back of Fort St. Louis where there is an important coaling station and repair shop without being shadowed by some private apparently detailed for the purpose. While overhauling my outfit I could see that every bag had been carefully searched -- nothing, of course, was missing. Through some sort of feigned misunderstanding I was unable to get back my expensive bill of health -- perhaps they thought I might alter the date and use it in Guadeloupe (above Dominica), the next French island. I had hoped to bluff the harbor-master at Dominica, but with my French bill of health gone, I could not do otherwise than obtain a new paper for Dominica -- the officials saw to that -- and it was just as well in the end for I met with the same officiousness that greeted Captain Slocum when I arrived at Roseau.

It had been raining and the deep, old-world gutters were full, miniature canals in which the broken shell of a coconut might be seen sailing down to the sea like the egg shell of Hans Christian Andersen. Apparently most of the refuse of the town is carried off in these gutters. But the canal gutters serve another purpose -- they wash the feet of the country people. One sees a woman whose muddy or dusty feet proclaim her to be from the country, walking into town with a monstrous burden on her head. She will suddenly stop on the edge of the sidewalk and balance on one foot while she carefully lowers the other into the running water of the gutter. She may at the same time be passing the time o' day with some approaching acquaintance half a block away. Their conversation seems to have a universal focus for any distance under a quarter of a mile -- the intensity is the same for three feet or a block.

Having washed her right foot with the nonchalance of a tightrope walker, she goes on her way till she makes such a turning as will bring her left foot alongside the gutter, and she proceeds as before.

It was usually in the afternoon that I saw that most picturesque sang mêle, the creole of Martinique, unaffected by the so-called advance of civilization, wearing the dress of watered silk and the heavy gold ornaments, with just that faint trace of interesting barbarity that goes with the generous features, the wide-spread eyes and the blue-black hair. She is a reminder of creole days of French Louisiana -- the coarser progenitor of our so-called "creole." I could see that most of these women were married, by the sign of the madras qualandi which is in reality a silk bandana tied on the head turban-wise, one corner knotted and stuck upright above the forehead like a feather. The unmarried women wear the madras in the usual manner, that is, without the knotted corner upright.

That these women are beautiful there is no denying ; the skin though it may be dark is very clear and the eyes give a frank open expression and by reason of their position seem to diminish what African coarseness may have been left in the nose. The nose may be flattish and a bit heavy but the broad, even high forehead, wide-spread eyes and perfect teeth counteract this effect so that it is hardly noticeable. One finds these people a delightful contrast to the rawboned creole of the English colonies with her male-like figure and eccentricities of hair, nose, lips, hands and feet.

There was a refreshing spirit of enterprise -- we get the word from the French -- and of varied interests that were a relief after having seen the "live and bear it" spirit of the English islands. The people of Martinique are industrious and they are happy -- the one naturally follows the other. In the market I found nearly all the vegetables of the temperate climate besides those of the tropics. They are now extensively growing the vanilla bean and the Liberian coffee is excellent. The wines which they import from France are inexpensive. In drinking the claret they dilute it with water which is the French custom and is as it should be. One might live very comfortably in Fort de France. There were electric lights and book stores where one could buy the current French magazines -- illustrated, humorous and naughty. I bought several. There was just one step in their enterprise which I did not appreciate and that was the cultivating of home-grown tobacco -- Tabac de Diable.

My walks about town were for the most part sallies from the hotel during intermissions between showers, for it rained almost continually for the entire week. These sallies I alternated with periods of writing in the quiet little cabaret where an occasional acquaintance would sit down for a chat, my French taking courage from day to day like an incipient moustache. I usually occupied a marble-topped table under an open window by which bobbed the heads of passersby.

What front the Hôtel de l'Eurôpe boasts, faces toward the savanna in the middle of which stands the statue of the Empress Josephine. Here she stands, guarded by a high iron fence and surrounded by seven tall palms, their tops, towering to a lofty coronet, above her head, seemed to claim her after all as a child of the West Indies. She is looking pensively across the bay towards Trois Îlets where she may or may not have been born and where so many sentimental steamer-deck authorities on the West Indies may or may not have made pilgrimages to the parish church and perhaps to the ruins of the La Pagerie estate. That she spent a considerable part of her West Indian days in Saint Lucia there can be no doubt and I will say for the benefit of the steamer-deck authorities that there is a very strong likelihood that she was born in that island. Was it some ironical whim that tempted the sculptor to impart a wistfulness in her face which seemed to carry her thoughts far beyond Trois Îlets and across the channel to the little plantation on the Morne Paix-Bouche and perhaps still farther, along that half mythical chemin de la Longue Chasse, which I discovered some time later on an old map of Saint Lucia, leading from the Dauphin quarter down to Souffrière? I have often wondered whether it was mere chance that impelled the sculptor to express that sign of parturient womanhood for which Napoleon longed and the lack of which caused one of the most pathetic partings in history.

One morning I was honored by a call from the clerk of the hotel. A delegation from the Union Sportive Martiniquaise et Touring Club Antillais wished to wait upon me at four o'clock in the afternoon -- would I receive them? At four, then, while I was sitting at my table in the cabaret, the delegation of four came, headed by a fiery little man of dark hue -- but a thorough Frenchman. His name was Waddy and I came to like him very much. The committee was very much embarrassed as a whole and individually like timid schoolgirls, but if they blushed it was like the desert violet -- unseen.

Would I do them the honor to be entertained for the rest of the afternoon? I said that I should be delighted -- and felt like a cheap edition of Dr. Cook. Waddy explained to me that the club was very much interested in my cruise and that it was their intention to become familiar with the other islands of the Antilles. The members of the club were for the most part eager to visit the neighboring islands but they were too timid to trust themselves to anything smaller than a steamer and while there was more or less frequent communication by steamer with Europe there was no inter-island service except by sloop. My coming in a canoe had set them a wonderful example, he told me.

We then walked to the jetty and were rowed out into the harbor to visit a West Indian schooner of the type that sailed from Martinique to Cayenne and upon which Waddy hoped the Club as a whole could some day be induced to cruise. She was an old Gloucester fisherman of about eighty tons and perfectly safe (I assured Waddy) for the use of the Touring Club Antillais. Having surveyed the schooner we were rowed ashore where a carriage awaited us. We then drove by a circuitous route, carefully planned out beforehand to include the various sights of note in the town, to the rented house in the Rue Amiral de Gueydon where the Union Sportive Martiniquaise et Touring Club Antillais thrived.

I was escorted to a room on the upper floor where the Union Sportive Martiniquaise et Touring Club was already gathered. To my intense embarrassment, the President of the Union Sportive Martiniquaise et Touring proceeded to read off a long speech from a paper in his hand. What he said I managed to understand for the most part but it concerns us little here. I replied to the members of the Union Sportive Martiniquaise to the best of my ability -- in French -- and what I said I know but they did not understand -- neither does that concern us in this writing. After a pleasant stramash of verbal bouquets we were served with refreshments which consisted of champagne and lady fingers. Champagne is not a rare beverage in the French islands, but I did not imagine that I should see it used with the familiarity with which the German treats his morning coffee ; I mean the habit of dipping his toast in it. But dipping seemed the custom and into the champagne went the lady fingers of the Union Sportive, and mine. To me these people were warmhearted and impulsive and as I got to know them, thoroughly likable.

According to my almanac, it was Easter Sunday and I almost felt ashamed of my morning cigarette as I left the hotel for a little stroll before I should sit down to my notes at the marble-topped table. But somehow or other I thought I must be mistaken in the day. While there were few people on the streets, to be sure, all the small shops were open. I walked over to the covered market and to my surprise I found that open also but most of the business had already been transacted. But the large stores, emporiums and magasins as they were called, were closed. Then I passed a church and saw that it was packed. Another church was packed. The priests were doing a thriving business and I realized that perhaps after all it was Easter Sunday. I did not know that with the ending of Lent the people were having a last injection of the antitoxin of religion to inoculate themselves from the influence of Satan which was sure to follow on Monday. And it was on account of Monday that the small shops and the market were open, for everybody went to the country for the Easter holidays, that is everybody who was anybody, and they left the town to the proletariat. Those who were fortunate enough to be able to spend the week in the country must need get their last fresh supplies at the market and the little necessities such as sweets, tobacco and so on which were apt to be forgotten in the press of Saturday could yet be bought on the way home from church.