Alone in the Caribbean

CHAPTER III.

KICK 'EM JINNY

I FIRMLY believe that it was my lucky bug that did the trick, although under ordinary circumstances I would not carry a tarantula for a mascot. It was on my last night at Île-de-Caille, and as I crawled up through the hatch of my upper story abode, something black stood out in the candle flicker against the wall. Before I knew what it was, instinct told me that it was something to look out for and then I noticed the huge hairy legs that proclaimed the tarantula. Of course, I could not have him running around as he pleased so I took the under half of a sixteen gauge cartridge box and covered him before he had time to think of jumping. The box, which measured four and a half inches square, was not too large for I nipped his toes as I pressed the pasteboard against the wall. Then I slid a sheet of paper between him and the wall. It was no trick at all to superimpose the upper half of the pasteboard box, slip out the paper and push the cover down. He was mine. And a good mascot he proved to be although I gave him a rough time of it in the jumble of sea off Kick 'em Jinny.

Kick 'em Jinny is the sea-mule of the Grenadines. In a prosaic way the cartographer has marked it "Diamond Rock," and then, as if ashamed of himself, has put the real name in small letters underneath. So "steep-to" that a vessel would strike her bowsprit on its sides before her keel touched bottom, Kick 'em Jinny rises from a diameter of a quarter of a mile to a height of nearly seven hundred feet. Cactus-grown, with no natural resources, one would scarcely expect to find on it any animal life other than a few sea fowl. Yet, besides myriads of screaming gulls, boobies, pelicans and wild pigeons, here are goats, the wild descendants of those left by the Spanish pirates, who used to plant them as a reserve food supply that would take care of itself.

The rock lies a third of a mile to the northward of Isle de Ronde, with the jagged Les Tantes a scant two miles to the eastward. With the trades blowing fresh from the northeast the lee tide runs through the passage between Isle de Ronde and Les Tantes at a rate of three knots an hour, whirling past Kick 'em Jinny in a northwesterly direction -- at right angles to the wind and sea. The weather tide in returning runs in almost the opposite direction at the rate of a knot and a half. It must be remembered that the constant northeasterly winds move a surface current of water toward the southwest so that this confluence of wind and current makes a tide rip on the weather side of Kick 'em Jinny, from which its name is derived.

Now you may ask, as I did when I discussed the matter with my friends of St. George's over tall, cool glasses of lime squash -- Why not sail under the lee of Kick 'em Jinny? If I sailed under the lee of the rock I should lose much valuable ground to windward while if I fought it out along the back or weather side of Ronde and Kick 'em Jinny and then made a port tack to Les Tantes I should be in the best possible position for my jump to Carriacou. That point settled, it was a question of tides. With the lee tide running to the north-north-west I might not be able to clear the rocky windward shore on my starboard tack, and it would be very difficult to claw off on the port tack, the latter being to eastward and away from shore.

With the weather tide, however, I could work my way off shore in case of necessity, but I should be fighting the current as I advanced on the starboard tack. With the weather tide I should encounter the rougher sea, and it was here that the Yakaboo would meet her pons asinorum, to carry out the idea of the sea-mule.

Many bets had been offered and some had been taken at St. George's that I would not reach Carriacou, which implied that the cruise would come to an end off Kick 'em Jinny. But I put my faith in one -- my Man Friday, who had instructed me in the mysteries of "de lee an' wedder toid," and he had shown me how to watch the weather in regard to the changes of the moon. During my stay on Île-de-Caille, I watched the quarters come and go and kept track of the moon in order to note the changing of the tides. I finally selected a day when the second quarter had promised steady winds, with the weather tide beginning to run at nine o'clock in the morning. If there should be any doubt as to the weather for that day, that doubt would be settled by the time the weather tide had started. With everything as much in my favor as possible I would make the attempt.

I slept that morning till the sun had climbed well up the back of Caille, for when I awoke the warm day breezes were filtering over me through the mosquito bar. I must have eaten breakfast, but later in the day I was puzzled to remember whether I had or not. My mind was not in the present, nor anywhere near my earthly body -- it was living in the next few hours and hovering over that stretch of water to the eastward of Kick 'em Jinny. Bynoe and his crew were also going to sail northward to Cannouan in the Baltimore, and I remember standing among the rocks of the whale cove bidding good-bye to the rest of the people. The few shillings I gave them seemed a princely gift and tears of gratitude streamed down the black shiny face of the cook when I presented her with a bottle of rheumatism cure.

The tide would turn at seven minutes after the hour and three minutes later the Yakaboo was in the water. By the feel of her as she bobbed in the heave of the sea I knew that the fight was on. With long rhythmic strokes the whaleboat swung out of the cove, the canoe moving easily alongside like a remora. Cautiously we rowed around the north end of Caille, seeking the currentless waters close to shore. When we reached the windward side of the island we made sail. It did not take many minutes to see that the canoe would be left alone in her fight with Kick 'em Jinny for the whaleboat, with her ballast of "rock-stone" and her twelve hundred pounds of live weight to steady her, caught the wind high above the seas with her tall rig and worried her way through the jumble in a way that made me forget, in a moment of admiration, my own sailing.

But I had other business than that of watching the whaleboat. As I hauled in the sheet to lay the canoe on the starboard tack, a sea seemed to come from nowhere and with scant invitation dropped aboard and filled the cockpit. It was like starting up a sleeping horse with an inconsiderate whip lash. The Yakaboo shook herself and gathered herself for that first essay of windward work. Try as she would, she could find no ease in the nasty, steep sea, and instead of working well along the shore of Ronde in the wake of the whaleboat, she barely crossed the channel from Caille and fetched up at the southern tip of the island.

On the port tack to sea she did better, although the weather tide running abeam carried us back off Caille. We made perhaps a mile to the eastward and then I decided to try the starboard tack again. The canoe did still better this time -- for a while -- and then we found ourselves in the toils of Kick 'em Jinny. The tide was now running with full force directly against us and at right angles to the wind. There seemed to be no lateral motion to the seas, they rose and fell as though countless imps were pushing up the surface from below in delirious random. One moment the canoe would be poised on the top of a miniature water column to be dropped the next in a hollow, walled about on all sides by masses of translucent green and blue over which I could see nothing but sky. The stiff wind might not have been blowing at all, it seemed, for the sails were constantly ashake, while the centerboard rattled in its casing like the clapper of a bell. It was not sailing -- it was riding a bronco at sea.

Bynoe, who was carrying my extra food supply in the whaleboat, was now making frantic motions for me to turn back. I had already decided, however, that the canoe would worry her way through and I motioned to the whalers to come alongside. With the two boats rising and falling beside one another, as though on some foreshortened see-saw, the stuff was transferred from the whaleboat to the canoe. As the whaleboat rose over me the men dropped my bags into the cockpit with an accuracy and ease of aim acquired from years of life in just such jumping water as this. The canoe sailor must at times not only be ambidextrous, but must also use feet and teeth ; in fact, he must be an all around marine acrobat. What wonders we could perform had we but retained the prehensile tail of our animal ancestors! So with the mainsheet in my teeth and my legs braced in the cockpit, I caught the bags with one hand and with the other stowed them in the forward end of the well under the deck. A large tin of sea biscuit, a cubical piece of eight-cornered wickedness, which would neither stow under deck nor pass through the hatches, required two hands for catching and stowing and a spare line to lash it in place just forward of my blanket bag. Then they screamed "Good-bye" at me across the waves, while I yelled "Yakaboo," and we parted company. Of that row of six black faces, two I shall never see again for they have since been lost in the very waters where we said "Good-bye."

Taking quick cross-bearings by eye I could detect from time to time changes in the position of the canoe and I knew that there was some advance to the northward. Finally we were so close to Kick 'em Jinny that I could see the chamois-like goats stuck on its sides like blotched rocks. All progress seemed to cease and for three-quarters of an hour I could detect no change of position. No stage racehorse ever made a gamer fight than did the Yakaboo against her ocean treadmill. The whaleboat was now a vanishing speck to the northward like a fixed whitecap. I began to wonder whether I should stick in this position till the coming of the lee tide. I remember contemplating a small strip of beach on Les Tantes where, in a pinch, I might land through the breast-high surf with enough food to last till the whalers might see some sign that I could put up on the rocks.

Suddenly a blinding flash brought my attention from Les Tantes to my cockpit. It was the tin of sea biscuit. The water sloshing in the cockpit had softened the glue of the paper covering. Finally, an extra large wave, a grandfather, swept the paper entirely off, leaving the shiny tin exposed to the brilliant sun. With a sweep I cut the line, and the next instant I was mourning the loss of a week's supply of sea biscuit.

The forward compartment now proved to be leaking, through the deck as I discovered later, at just the time, when, if the canoe had any soul at all, she would keep tight for my sake. I shifted my outfit as far aft as possible and sponged the water out by the cupful with one hand ready to slam down the hatch in advance of a boarding sea. It was done -- somehow -- and as a reward I found the canoe was working her way into easier seas. Then she began to sail and I realized that Kick 'em Jinny was a thing of the past. I lay-to off Les Tantes, having traveled three miles in two hours. We had not conquered Kick 'em Jinny, we had merely slipped by her in one of her lighter moods. But the canoe had stood the test and by this I knew that she would carry me through the rest of the channel to Saint Vincent. What her story would be for the larger openings of from twenty-five to nearly forty miles yet remained to be seen.

With her heels clear of Kick 'em Jinny the Yakaboo traveled easily in the freer waters and before the tide could draw me out into the Caribbean I was well under the lee of Carriacou. Another half hour and I should have had to fight for six hours till the next weather tide would help me back to land.

Late in the afternoon, I stepped out of the canoe on the uninhabited island of Mabouya, which lies off Carriacou. The beach where I landed was typical of the few low-lying cays of the Grenadines. The sand strip, backed by a cheval de frise of cactus, curved crescentlike, the horns running into sharp, rocky points which confined the beach. The only break in the cactus was a clump of the dreaded manchioneel trees and here I decided to pitch my tent.

Barbot, in relating the second voyage of Columbus, says : "On the shore grow abundance of mansanilla trees, not tall, but the wood of them fine, the leaves like those of the pear tree, the fruit a sort of small apples, whence the Spaniards gave them the name ; of so fine a color and pleasant a scent, as will easily invite such as are unacquainted to eat them ; but containing a mortal poison, against which no antidote has any force. The very leaf of it causes an ulcer, where it touches the flesh, and the dew on it frets off the skin ; nay the very shadow of the tree is pernicious, and will cause a man to swell, if he sleeps under it." I thought I would take a chance -- perhaps the manchioneel had become softer and more civilized since the time of Columbus.

If there were any joy in the feeling of relief as I walked up that lonely beach, I knew it not. Tired as I was, I could only think of the hard work that I had to do before I could lie down to rest. The Yakaboo had been leaking steadily all day long and she now lay where I had left her in a foot of water, with my whole outfit except my camera submerged. This did not mean that everything was wet, for my own muslin bags, honestly oiled and dried, would keep their contents dry, but there was the canoe to unload, bail out and drag ashore. There was firewood to collect before dark, and I should have to work sharp before sundown, for there were also the tent to pitch, the supper to cook, and the log to write.

For a moment I stopped to look at the glorious sun racing to cool himself in the Caribbean, and I gave thanks for a strong body and a hopeful heart. In two hours I was sitting under the peak of my tent on my blanket roll, watching my supper boil in a little pail over a lively fire of hard charcoals. The Yakaboo, bailed out, high and dry on the beach, skulked in the darkness as though ashamed to come near the fire.

It is always easy to say "in two hours I was doing so and so," but to the man who lives out of doors and is constantly using his wits to overcome the little obstacles of nature those "two hours" are often very interesting. As a rule, one is tired from the day's work and if accidents are going to happen they are apt to happen at just this time. The early stages of fatigue bring on carelessness, and to the experienced man the advanced stages of fatigue call for extreme caution. Before unloading the canoe, I should have decided just where I would place my tent and then I should have beached the canoe immediately below the tent if possible. As it was, the Yakaboo was sixty yards down the beach and upon returning from one of my trips to her I found that a spark from the fire had ignited my oiled dish bag which was burning with a fierce heat. This had started the bag next to it which contained my ammunition. With one leap I landed on the precious high-power cartridges and began to roll over and over in the sand with the burning bag in my arms. What would have happened had one of my nine-millimeter shells exploded? I had been careless in arranging my outfit upon the sands when I built the fire.

Troubles never come singly -- neither do they travel in pairs -- they flock. I remember the difficulty I had in starting the fire. The tin in which I carried my matches was absolutely watertight -- I have proved that since by submerging it in a bucket of water for two days and nights. And yet when I came to open the tin I found that the tips of the matches were deliquescent. It was my first experience in tropical cruising and I had not learned that the heat of the sun could draw the moisture out of the wood of the matches, condense this moisture on the inside of the tin, and melt the tips. I found some safety matches tucked away in the middle of my clothes bags and they were dry. This became my method of carrying matches in the future. The natives carry matches in a bamboo joint with a cork for a stopper.

And now that I have taken you into my first camp in the islands I shall tell you briefly of the various parts of my outfit as it was finally shaken down for the cruise.

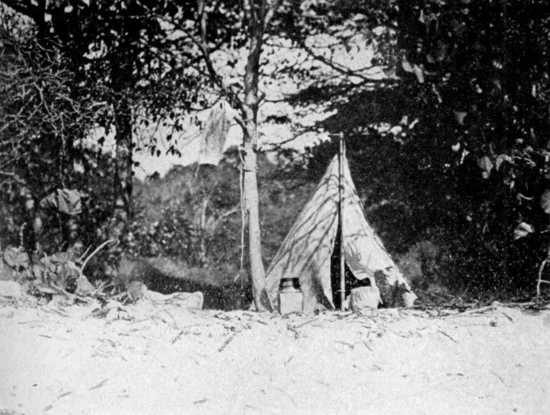

My tent was of the pyramidal form invented by Comstock, seven feet high with a base seven feet square and having the peak directly over the center of the forward edge. In back was a two foot wall. It was made of a waterproof mixture of silk and cotton, tinted green, and weighed eight pounds. My mainmast served as a tent pole, and for holding down I used seventeen pegs made of the native cedar, which is a tough, hard wood and not heavy. For my purposes I have found this the most satisfactory tent for varied cruising, as I could use it equally well ashore or rigged over the cockpit of the Yakaboo when I slept aboard. Let me here offer a little prayer of thanks to Comstock. You will find some "improvement" upon his idea in almost any outfitter's catalogue and given any name but his -- one might as well try to improve it as to alter a Crosby cat.

My Comstock tent.

For sleeping I had two single German blankets, weighing four pounds each. In place of the usual rubber blanket, I used an oiled muslin ground cloth. My blankets were folded in the ground cloth in such a manner that upon drawing them from the blanket bag, I could roll them out on the ground ready for turning in. The blanket bag was made of heavy oiled canvas with the end turned in and strapped so that even when it lay in a cockpit half full of water its contents would still remain dry. One blanket used with pajamas of light duck would have been ample, so far as warmth goes, but for sleeping in the cockpit the second blanket served as a padding for the hard floor.

As for clothes, I started out with a heterogeneous collection of old trousers, shirts and socks, which, according to the law of the survival of favorites, petered out to two pairs of light woolen trousers, two light flannel shirts, and two pairs of thin woolen socks. I indulged myself in half a dozen new sleeveless cotton running shirts, dyed red, B.V.D.'s to correspond, and a dozen red cotton bandana handkerchiefs. For footgear, I carried a pair of heavy oiled tan shoes and pigskin moccasins. A light Swedish dog-skin coat and a brown felt hat with a fairly wide brim, completed my wardrobe.

For cooking I had the "Ouinnetka" kit, of my own design, consisting of three pails, a frypan, two covers, a cup, and two spoons, all of aluminum, which nested and held a dish cloth and soap. There were no handles, a pair of light tongs serving in their stead. This kit, which was designed for two-man use, weighed a trifle under three pounds.

The rest of my working outfit consisted of a two pound axe, a canoe knife, a small aluminum folding candle lantern, two one-gallon water cans, and a ditty bag, containing a sight compass, parallel rule, dividers, hypodermic outfit, beeswax, and the usual odds and ends which one carries. For sailing I used a two-inch liquid compass. This working outfit totaled forty-three pounds. Had the "butterfly" continued in service, its weight would have added a pound and a half.

My camp at Mabouya.

My food at the outset brought this weight up to eighty pounds, but as I later on got down to chocolate, erbswurst and the native foods, there was a reduction of from twenty to thirty pounds.

The heaviest single unit of my whole outfit was a quarter-plate Graflex, which, with its developing tank and six tins of films, added twenty-six pounds. A nine millimeter Mannlicher, .22 B.S.A., 38-40 Colt, a deep sea rod and reel, shells, and tackle brought the total up to 120 pounds. I might as well have left out my armament and tackle for when cruising I find little time for shooting or fishing -- I would rather travel.

My charts, twelve in number, had first been trimmed to their smallest working size and then cut into eight-inch by ten-inch panels and mounted on muslin with half an inch separating the edges so that they could be folded to show uppermost whatever panel I happened to be sailing on. The charts with my portfolio I kept in a double bag in the aft end of the cockpit.

The various parts of my outfit were in bags having long necks which could be doubled over and securely tied. These were made of unbleached muslin, oiled with a mixture of raw and boiled linseed oil and turpentine. After a wet bit of sailing, when the canoe had at times literally gone through the seas and there was water in every compartment, it was a great comfort to find the entire outfit quite dry.

The weight of the Yakaboo, with her rig and outfit aboard, varied from 260 to 290 pounds -- not much more than that of an ordinary rowboat.

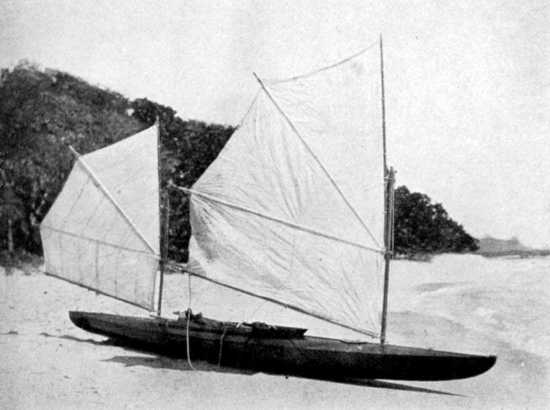

Loaded and ready to get off.

Nothing is so unalloyed as the joy of pottering over a hot, little fire when the stomach cries out and the body tingles with the healthy fatigue of work in the open. My spirit was at ease, for the canoe had proven herself and even if she did leak, I was getting used to that -- as one becomes used to a boil on the neck. To lie on my blankets -- no bed was ever so welcome -- and to eat and watch the last light fade from the hills of Carriacou made me glad that I had been put on this earth to live. After supper the companionable purr of my faithful pipe made just the conversation to suit my mood. The night was soft and balmy, and as I lay and watched the brilliant constellations of the tropical night the lap-lap of the water on the smooth sand lulled me off to sleep.

CHAPTER IV.

CARRIACOU-MAYERO-BEQUIA.

THE next moment I was sitting up, blinking into the fiery face of the sun that had slipped around the earth and was bobbing up again in the east.

It was not the sandy beach, the blue stretch of wind-livened water nor the picturesque hills of Carriacou, rising up before me, that alone brought happiness, for, as my eye wandered down the beach, I saw the buoyant, jaunty Yakaboo, and there came over me the happy satisfaction that the cruise was mine. My eye beheld her with the fondness of a parent for its child -- if only she did not leak.

Not until I had cooked and eaten breakfast and was stowing my outfit into the canoe did I think of the mascot I had brought with me from Caille. I found his house in the forward end of the cockpit, unglued by the wash of the day before and empty. I am not sentimental by nature and I did not mourn his black hairy little body, which no doubt, by this time, was being carried far out into the Caribbean. I did thank him, or rather her, for I found out afterwards that it was a female, for the service she had rendered as a mascot in my sail around Kick 'em Jinny. I did not know, in fact, that she was still with the ship and would be my mascot for some time to come.

When I ran alongside the jetty of the pretty little town of Hillsboro, on the shores of Carriacou, a blue-jacketed sailor pointed to where I might beach the canoe, and said, "Mr. Smith is expecting you in his office," a prosaic remark, more fitting to the tenth floor above Broadway than to the beach of a West Indian island. I had scarcely beached the canoe and was walking across the hot stretch, curling my toes under me to ease my soles on the blistering sands, when Mr. Smith met me, a tall, spare figure, accentuated in its leanness by the bulky helmet of the tropics. I liked him instantly. He was a man of about fifty, strong, energetic and young for his age. There was a bit of a brogue in his speech -- he was an Irishman -- with a university training and cultured as such men usually are, but still with an Irishman's fondness for the world. Perhaps my liking was part of a mutual feeling for he immediately asked me to spend a few days with him at Top Hill. A cozy berth was found for the Yakaboo in a boatshed near by, built, for the sake of coolness, like the cotton ginnery of St. George's, with open sides.

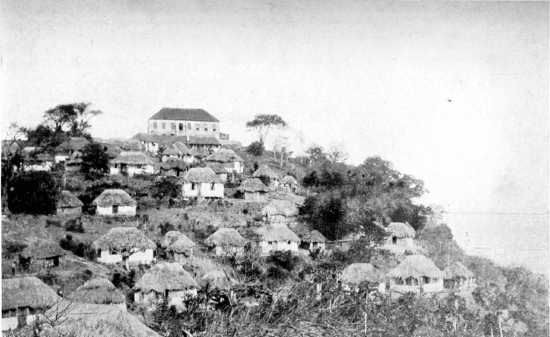

On Carriacou looking north.

Carriacou might be called the Utopia of the Grenadines. It is here that the work of one man stands out and is not lost. Officially Whitfield Smith is known as the Commissioner,* in reality he is a potentate, while among his people he is known as "Papa."

* Whitfield Smith has been Commissioner at Grand Turk since 1915.

Paternal is the rule of this man, which, after all, is the way all governing should be done. And still with his paternal feeling and his kindness, there is no undermining familiarity. Justice, one feels, holds out her delicately balanced scales and there is no chance for her eye to pierce the blindfold. As in all the West Indies, there is very little crime, petty theft and small squabbles being the principal offenses. Swearing is a punishable offense and one hears but little profanity. The detection of crime is no disgrace and one does not lose caste upon being haled into court. Let the prisoner be convicted and imprisoned and he is forever disgraced.

The curse of the black man is laziness and the curse of the islands is the ease with which life may be sustained. To these may be added a warped idea regarding the tilling of the soil. There is deep rooted from the times of the old planters the West Indian notion that no gentleman dare use his hands in manual labor. The West Indian negro who has received a small smattering of an education spurns hard work and goes to the towns, where he can obtain a position as a clerk in a store. In this way the fields come to be neglected and labor is actually imported for the tilling of the soil. The black man wants to attain his estate by revolution -- not physical but mental -- while this can only come by a long process of evolution. In his period of transition he should be guided by the highest type of white man, broad minded ; virile, keen and human. Given authority to govern a small community, such as that of Carriacou, and the right man's influence for good among the people is infinite. The ease with which he can accomplish reforms is astonishing. For instance, on my first day at Carriacou I remarked to Smith that there seemed to be scarcely any mosquitoes, indeed, I had not seen any, a remarkable circumstance in view of the fact that the land immediately to the southeast of the town was low and swampy.

"You will have a hard time finding any on the island now, although we have a few in the rainy season.""Kerosene and mosquito bar?" I asked.

"No, million-fish. In Barbados," continued Smith, "it was noticed that on certain freshwater ponds there seemed to be no mosquitoes. Upon investigation it was found that these ponds were the habitat of the 'tap minnow' (Girardinus pocciloides) or 'million-fish,' as it is called, and that these small fellows ate the larvae of the mosquito as they rose to the surface of the water. The fish were introduced to other ponds, water tanks and rain barrels, with the result that there was a considerable reduction of the pest. I sent for some of the fish,* and put them on exhibition in a large glass jar in my office. Then I asked the people to bring in all the larvae they could find floating on the top of the water in rain barrels, tanks and so on. As soon as the larvae were put in the jar, the million-fish swam to the surface and gobbled them up. Then I told the people that if they put million-fish in all the places where mosquitoes breed, the eggs would be eaten up and there would be no more malaria, filaria, and so forth. It was the best kind of an object lesson. The fish were put in all the small ponds, tanks and barrels and they multiplied till there were enough to distribute all over the island."

* The males are an inch long, silver-grey in color and with a

red spot on each side near the head. The females are

about an inch and a quarter long but have no red spot.

In a similarly easy manner he disposed of a troublesome labor problem. The British government allows six hundred pounds to be spent yearly for the maintenance and building of roads in Carriacou. The work is done by native women who receive nine pence a day or eighteen cents in our money. Smith found that there were more women dependent upon the road work for their livelihood than he could employ at one time and the solution was suggested by the so-called 'paternal system' used in St. Thomas. He secured a list of all the road workers on the island. Of this list he works forty each week, by rote, and in this way the government road money is fairly distributed. He is more like the owner of a large estate than an employee of the British government ruling a small island for a salary. I decided that there might be worse places to live in than Carriacou and that with a man like Smith on the island one's mind would not go altogether fallow. Perhaps my liking for the island was strengthened when I walked into a neat little store, not unlike the kind one finds in a new suburb of a progressive city. Here I could buy small cans of white lead and paint, commodities I could not find in St. George's, and I found sandpaper that had not lain in moldy disuse since the times of the pirates.

As the day cooled into evening, I walked out to the end of the jetty to contemplate the sunset and smoke a quiet pipe. To the west Mabouya, where I had camped the night before, hung a persistent little patch which resisted the efforts of the trade to wash it away towards the horizon of ragged clouds. To the north jagged Union rose, the highest of all the Grenadines, but here my peace came to an end.

There had been one house in which the owner had lived at the top of the hill.

"What is your reputation?" broke upon my ears. I faced about to find an officious native in a white linen suit, cane and Panama hat standing by me. While I was groping feverishly in my mind for a suitable reply, a native policeman stepped up and hustled off his compatriot before I should forever disgrace myself in this island of soft language. I was no longer in the mood for sunsets and I turned shorewards to find Smith preparing for the drive to his home at Top Hill. The twilight merged into the pale light of the new moon and as we slowly climbed the hills Smith talked about his island.

"That is our botanical garden," he said, pointing out an acre or two of planted land that looked like a truck garden, "limes, water lemons, and a flower garden so that we can make up a bouquet when we have a wedding, you know."

On our way we met a Yellow Carib from Demerara. He was the second Carib that I had seen and joy came with the thought that in Saint Vincent I should find more of them, the last remnant of the Yellow Carib in the Lesser Antilles.

We had no sooner alighted in the courtyard at Top Hill than Smith bounded ahead of me and, standing on the top step of his verandah waited for me with outstretched hand, and said, "Welcome to Top Hill." There was a warmth about it that I shall never forget.

With us was MacQueen, an engineer, who might have been taken out of one of Kipling's Indian stories. The two were in a mood for stories that night, stories, for the most part, of the natives, showing their craze for the spectacular, their excitability, and the ease with which they can be fooled.

"Did you ever," -- there was a slight burr in the "ever," -- "did you everr hear the one about New Year's Eve at Goyave, Mac?""Not in recent years," said Mac -- and we have the story.

"Times had been prosperous and the priest was looking forward to a large contribution at the mass which was to see the Old Year out and the New Year in. He had arranged an impressive ceremony, not the least part of which was the shooting of fireworks on the precise stroke of twelve. Rockets were planted in the churchyard behind the gravestones, and a boy was stationed to touch off the fuses at the given time. The church was packed and in the dim candle light the priest struck awe into the souls of his congregation as he told them what a hell they were surely going to if they did not repent. He spoke with the fervor of a man working for that which was nearest his heart -- money.

"The emotional natives became conscience-stricken as they thought, childlike, of their many misdeeds and there was the terror of hell in that blubbering crowd. But there was a chance -- a very small one, in truth and the priest pointed to that heaven for which they could make a fresh start with the coming of the New Year. As he raised his hand aloft, the boy thought it was the signal for the fireworks. In the dramatic pause that followed the priest's warning, the awesome silence was intensified by the spasmodic sniveling of the people.

"Suddenly there was a blinding flash, and a hissing rocket spurned its way heavenward. Another rocket, and then a bomb exploded. The boy was doing his part well. To the frightened congregation the end of the world must be at hand. With a roar of terror, they rushed from the church taking their pennies with them."

"O Lord," said Smith, the tears rolling down his cheeks, "the poor priest was out the price of the fireworks and lost his contribution."

"No doubt," said Mac, "he more than made up for it in confession fees for he knew that his people were uneasy of conscience."

"And talking about graveyards reminds me of a burial we once had during the rainy season," continued Smith. "A man had died of fever one hot afternoon and I decided to have him buried that night. He was laid out and I ordered a carpenter to make a box for him. By ten o'clock the box was ready and we started down the hill. There was no moon and the clouds shut out the starlight. It was black as pitch and before the days when we had a good road up from town. There were three of us carrying the corpse, myself, the doctor and my man, while the priest walked on ahead chanting the Resurrection. We had no sooner started than it began to rain. Not an ordinary rain or a shower, but the torrential downpour of the tropics. In a short time the roadway was a slippery downward surface over which we were fighting to keep the box with its contents from getting away from us. All this time that lazy beggar was walking ahead of us chanting in a loud voice for us to follow. The doctor, who was a crusty old Scotsman, slipped and fell, pulling the box down with him. Then, before we could take it up again, he gave it a push and it coasted down the hill, catching up the priest on its way. As the black-robed priest disappeared astride the coffin, the doctor yelled, 'Gae 'lang wid ye and yeer Resurrection.'

The next day was the fifth of the moon. In these latitudes where the moon seems to have a decided influence upon the weather, there is a strong tendency towards squalls on or about the fifth day of the new moon. Captain Woolworth, in his book "Nigh onto Sixty Years at Sea," mentions the fact that whenever he ran into trouble it was almost invariably on the fifth day of the new moon. Most of his voyages were made in the tropics. Smith called my attention to the weather on this day and I was careful to note every fifth day during the rest of my six months in the tropics. Almost without fail, from the third to the sixth day and generally on the fifth day of the first quarter there was trouble at sea. Conditions generally were unsettled. Heavy squalls would blow down like the beginnings of small hurricanes. Often I could count four or five squalls at one time whipping up as many spots on the sea to a fury of white caps and spindrift. There is something uncanny in the way in which the moon seems to affect the weather in these parts and I have often thought that the superstition of the negro is not to be wondered or sneered at.

The next day the weather was settled and continued so for the rest of that quarter.

While overhauling my outfit which I had dumped in a corner of Smith's office I again came upon my little mascot. I was untying a bag containing a few small bits of Carib pottery, which I had dug up near Sauteurs in Grenada, when a black fuzzy object jumped from the heap of duffle before me and scampered across the floor.

"Hello! Who's your friend?" asked Smith."Oh, that's my mascot," I answered, as I dashed after her on all fours.

"Devil a fine mascot! Why don't you get a nice loving snake? Here! Take this!" said Smith, as he handed me a paper box cover. Having recaptured the tarantula I told the story of the luck she had brought me on my sail around Kick 'em Jinny. I was afraid that she might get into my blanket some time and bite me, so I took her life and carried her hairy carcass in a cotton-padded pasteboard box. I believe that after death her spirit hovered over the masts of the Yakaboo and that she bore me no ill will, for luck stayed with me for the rest of the cruise.

Having remained over the fifth day, I sailed for new islands and landed on picturesque Frigate, which lies off Union. Here I found an abundance of wood and was soon enjoying the crackle of a little blaze. It was good to be a Robinson Crusoe again, if only for a few hours. Before me on the beach lay the Yakaboo, her porpoise-like body suggesting more of the fish than the boat. Across a shallow bay, floored with white coral sand that gave it the appearance of a marble floored pool, Union rose a thousand feet.

I could make out the houses of a village, climbing above the shores of the bay, the most remarkable of its kind in the whole range of the Lesser Antilles, for I found that here one may see a thousand natives, living in small huts clustered close together, in exactly the way their ancestors lived two hundred years ago, when they were first brought over from Africa. One change only from the early days -- that of clothing. The men wear trousers and shirts and the women wear skirts. Remove their civilized rags and you have them as they were in Africa. I have heard that in some of the smaller and even more out of the way cays of the Grenadines the natives live among themselves with no clothing but the breech cloth. May the eye of my camera see them thus in their natural state on some future cruise.

While I was cooking my chocolate, a little open boat had been sailing down the wind from the eastward. As she beached close to the Yakaboo, two black men jumped out of her while something in the stern unfolded its attenuated length and I recognized Walker, famous as the tallest man throughout these islands. I knew him before I saw him -- that is all of him -- for it takes two looks to get in his full height. My eye wandered up and down his length as one views a tall waterfall close by.

The British government had but lately taken over Union Island from private owners and it had been Walker's duty to survey and divide up the land so that it can be sold in small parcels to the natives. With the strength and perseverance of one charmed, Walker has carried his transit in the fierce noon heat and cut his lines through the brush. The soft tissue of his body has long since run off in perspiration so that there is little left for the sun to work upon. He goes about his work unmindful, wearing a flannel shirt with a double thickness over his spine and a large hat, which gives him the appearance of an animated umbrella. He has other dimensions besides height I found, one of them being breadth of heart.

No introduction was necessary for I had long since heard of the tall Walker, and he had expected my coming long before he made out the butterfly rig of the Yakaboo zigzag its way up to the beach on Frigate.

During our conversation I admitted some knowledge of drafting, upon which Walker said, "Come over to Union and help me finish a map of the island and then we can take off a few days for a little loaf." And so it came to pass that my little green tent remained in its bag in the forehold of the canoe and I became for a time an inhabitant of Union.

A span of not much more than three nautical miles separates the islands of Carriacou and Union and yet the natives of Union differ from those of her neighbor by nearly as many hundred years. Up to a short time before I landed on the island, Union had been owned by one man or one family from the time of its discovery. There had been one house in which the owner lived -- on the top of a hill. It was now occupied by Rupert Otway, who represented the British government. Another house stood "down de bay," in which the overseer had lived while the rest of the population -- slaves -- had lived huddled together in the towns of Ashton and Clifton.

In 1838 the slaves were freed and from that time the prosperity of the island began to wane. But the blacks continued to live there, holding no property, a few of them working halfheartedly for the white man and the rest dragging out a mere existence from the fish of the sea. Now the government has bought the island and the ideal thing is being done -- that is, the island is being divided into small plots, which are held out with every inducement for the native to buy. The cash price is cheap, from four to eight pounds per acre. There is also a system of payments arranged so that the most impoverished native can take up a small piece of land and from it work out the price to pay for it.

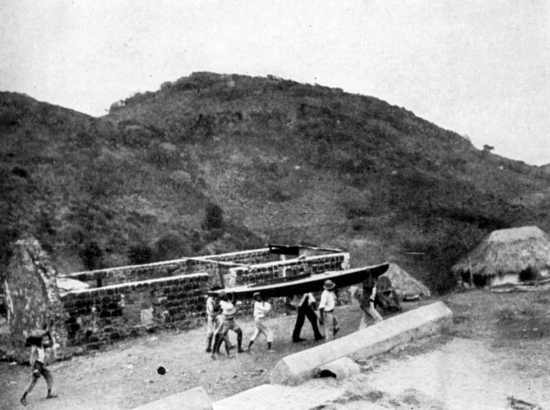

Cassava cake drying on a roof at Mayero. Ruins of the old estate house of the St. Hilaires in the background.

Not the least charm of these islands are the small private forts which one finds hidden in the bush which has overgrown the top of some hill of vantage, leaving scant evidence to the casual eye of some small pile of heavy masonry, the name and origin of which may have been long since forgotten. At the time of the Napoleonic Wars, when these islands were immensely rich in sugar, the estate owners were forced to defend themselves from the depredations of the privateers who infested these waters like the sharks that swim in them. For this purpose the old estate owners built private forts, one of which I found on Union, undisturbed in its state of dilapidation, four hundred feet above the sea, on the top of an isolated hill so overgrown with cactus that we had to cut our way to it.

Drying the cassava, Isle de Ronde.

Otway gave me a temporary Man Friday and after an hour's work with our cutlasses we had cleared away enough of the cactus so that we could walk about on the rampart. The top was five-sided, not an exact pentagon, about fifty feet in diameter. Here were four old cannon, lying as they had long ago sunk through their rotting carriages to rest, still pointing in the direction of their old enemies. One aimed at Mayero, two miles away, another covered the channel to the east, a third at one time dropped its death on Prune, while the fourth guarded the little bay where the ruins of the old storehouse or cabaret still stands. The romance of it all seemed intensified in the fierce noonday sun and it required little imagination to picture the days when fighting was an earnest sport. In the center stood the stepping for the flagstaff, the staff itself doubtless long since appropriated for the mast of some native sloop that may even now be resting deep down at the foot of Kick 'em Jinny. As the negro uses his horse till it drops, so he uses his sloop till at last a fierce squall gets him "all standing" and she sinks with her fear-paralyzed crew, leaving no sign, but a hatch or a broken bit of spar which drifts away towards the setting sun.*

Under the steps, which descend from the rampart, was the powder magazine, still intact, resembling an old-fashioned bake oven -- and this reminded me that I was due at Government house for luncheon.

The next day as I tried to leave Union, faulty navigation on the part of the skipper caused the centerboard of the Yakaboo to run afoul of a reef. The Yakaboo got the worst of it and I had to put back for repairs. I was on my way to Mayero. Both Walker and Otway were glad to see me back in Union and no sooner had I landed than they ordered their man to carry the canoe up the hill to a shady place, where a native carpenter could relieve me of the work of repairing her. This done, Otway seemed to remember that he owed Mayero a visit in his official capacity, Walker decided to take a day off, and the three of us sailed across in the little government sloop.

* In nearly all cases of loss at sea in these waters, there remains

not the slightest trace of the missing boat or crew and the

relatives blubber for a day or two, murmur,

"It wuz de will ob de Lard" and the tale becomes history.

Our landing on Mayero was a strange performance. The beach was steep-to with a fathom of water less than a boat's length from dry sand. We threw out an anchor astern and then ran the sloop inshore till her bowsprit hung over the surf. Taking off our clothes, we tied them together with our belts and threw them high up on the beach. Three splashes followed and we crawled ashore and dressed. After a climb of about fifteen minutes we gained the top of the island, where "Miss Jane-Rose" rules her little domain.

Mayero is one of those romance islands where in its stagnation one can trace a past once beautiful, now pathetic. At the time of the unrest in France, a cadet branch of the Saint-Hilaire family came to this island, thrived, and finally died with the ebbing fortunes of sugar cane. The last descendant of this famous old family, one of which was a lady-in-waiting to the Empress Josephine at Malmaison, still governs the island under a sort of feudal system. Her name is Jane-Rose de Saint-Hilaire,* and she is a bright, keen woman of about fifty, who rules her subjects with a firm hand and who talks well. The two hundred inhabitants, more or less, representing eighty families, on the island, are, for the most part, descendants of the slaves of the old Saint-Hilaires, and one can still see in their faces the vanishing trace of the French aristocracy like a thin outcropping of gold in the baser rock.

*Miss Jane-Rose died in Feb. 1915.

Each family is allowed to erect a hut free of charge of any kind. This hut is roofed with Guinea grass straw and sided with wattles, cut on the island, and plastered with mud. Most of the huts are floored with American lumber. Each able-bodied inhabitant is allowed as many acres as he or she cares to cultivate, on the metayer or share system. By this arrangement of land tenure, at the time of harvest the produce of the land, cotton and cocoa, is divided equally between the proprietress and the tenants. The people used formerly to give their share of the cotton to Miss Jane-Rose to dispose of for them, but they now sell it direct to the British government at better prices. The fisherman reserve for the proprietress a portion of each day's catch.

The people are essentially French and no religion other than the Roman Catholic is tolerated. Miss Jane-Rose officiates as priestess and occasionally a priest from Carriacou comes to celebrate mass. She also acts the part of mediator or judge in many disputes where no grave issues are involved. The people, generally, are a law-abiding lot and in eight years only two cases of importance have come within the jurisdiction of Whitfield Smith at Carriacou.

The little church, close to her house, was opened for our benefit, and it was with great pride that she exhibited the altar and the painted inscriptions on the walls. The building was nothing better than a wooden shed, an ant-eaten sanctuary into which small birds fly to nest through the holes in the roof. As we talked, a pathetic figure stole in to have a glimpse of "de mon in de boat," and to furtively touch his clothes to feel of what strange stuff they might be made. She was a little woman of sixty or more, not shrunken, for that would imply wrinkles, but lessened in size, as though she were slowly evaporating. Her face was still the face of youth, the sepia etching of a French beauty of the old days, the skin dark, somewhat transparent and of fine texture. It was a face beautiful and shapely in every line, the only negro feature that I could detect being the darkness of her skin. She seemed like some incautious mortal, under the spell of a Circe, with an appeal in her eyes to a deliverer who would never come.

With a parting gift of cassava cakes, taken from their drying place on the roof of one of the nearby huts, we scrambled down to the beach where we undressed and swam to the sloop, holding our clothes clear of the water. The wind had dropped with the setting of the sun, and we drifted back to Union in the moonlight before a soft, balmy air that carried no chill.

The next day I was more successful in leaving the island. Walker insisted upon accompanying me in his sloop to pilot me, as he said, through the intricate reefs. It afterwards turned out that he doubted the ability of the Yakaboo to make the passage to Bequia in safety. After three hours of cautious sailing, we ran ashore on Cannouan to cook our luncheon. Here it was that Walker taught me a new trick. The natives of the island had come down to have a close scrutiny of the strange man who was sailing about the islands in "de canoe," and I had come to the conclusion that their presence was far more picturesque than desirable. They handled everything, examined my dishes, and one of them even started to open my food bags. I swore at them, but they did not seem to understand. To my, "What the devil shall I do with these people?"

"Oh, I'll fix 'em," said Walker, at which he swept one arm toward them and then pointing at me yelled :"Get out! or 'de mon' will put a curse on you."

The words were magic. Profanity had made no impression, but the putting on of a curse by one who bordered on the supernatural -- that was something different! With one bound they cleared the place of our nooning and with another they were in the brush where for the rest of our stay I could see the tops of their woolly heads and the gleam of white eyeballs, curiosity and fear holding them balanced, as it were, at the nearest point of safety. After that, whenever I was troubled by curious natives I repeated Walker's "magic formula," Get out! Or I'll put a curse on you.

Six o'clock found the canoe and the sloop three and one half miles from West Cape on Bequia with a strong lee tide, that is, off shore, and the wind dropping. The sloop, being heavier with her rock ballast and her crew of three, had outsailed the much lighter canoe in the choppy seas and was leading somewhat to windward. Just as the sun was setting, I saw a number of fins coming down towards the canoe. I now got the greatest fright of my whole cruise. All my past experience as to the cowardice of the shark vanished, leaving a void into which fear rushed as into a vacuum. My imaginative brain could only attach those fins to a school of huge sharks, some of them probably larger than the canoe I was sailing in.

Of what avail would my seven inches of freeboard be to one of those fellows should he choose to slide his ugly head over the gunwale? Of what avail my armament of two rifles, one revolver, and one axe? At a maximum I had a bullet each for nineteen sharks and perhaps my trusty axe would finish up one or two, but here was a horde descending upon me. I remembered how sharks were in the habit of jumping clear of the water and tearing out the blubber on a whale's back ; at any rate, I thought, I would finish one or two of them before they dragged my mangled form into the sea and so forth -- oh, happy moment!

There was not the slightest use in altering my course to avoid them, so I held on and the next moment was in the midst of a school of snorting, playing porpoises. I could have jumped overboard and hugged them. I swore that the fun of graining them from the swaying footropes would never again be mine, nor would I even use their oil on my boots. To me the porpoise is henceforth a sacred animal. There were hundreds of them in the school and among them were blackfish of a considerable size. Playful and curious, they would make a dash with torpedo speed and then dive under the canoe or swerve around the ends, fascinating me with their wonderful grace and ease. One of them, making a slight miscalculation, bumped the centerboard and nearly upset the canoe. This made me think it safer to run off the wind and travel with them, presenting the edge of the board rather than the side. And so I kept them company till they had had their fun and resumed their travels.

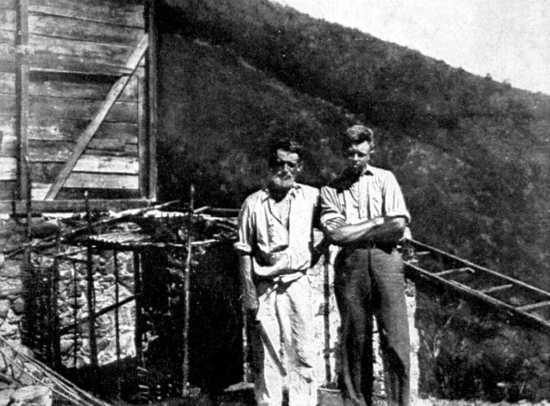

Preparing to leave Union. Walker sitting on the rail of his sloop and regarding Yakaboo doubtfully.

Coming back for repairs. Six men doing the work of two.

Some of them would jump clear of the water and with a half turn in the air would land on their backs with a resounding splash. It was their way of scratching their backs and I could almost see a grin of delight on their mouths. As they left me, twilight gave way, and I was alone in the starry night. Walker in the sloop was somewhere to windward -- out of sight. I had taken in sail and was now rowing, using for a guide Orion's Belt, suspended above the swaying top of the stubby little mizzen mast. As the moon rose, I could read the compass.

After an hour or so I must have fallen asleep, still rowing, for I awoke at nine o'clock, the oars still in my hands, to find that I was off my course and about a mile from West Cape, which now loomed up black in the distance. The current had swung the canoe around little by little as I had ceased to take notice of the compass till I was rowing northward instead of nearly due east. In another hour I was headed into Admiralty Bay in the lee of Bequia.

By that same law of compensation which I have already mentioned, I was now rewarded for a hard day of travel at sea. I shall never forget the beauty of that night as I slipped into the easier waters under the long arm of West Cape, which reaches from Bequia three miles out to sea. The moon was high in a brilliant sky across which the trade clouds rolled like a curtain, on their never-ending march to the Spanish Main. The Cape stood lofty and dark and bold and I could see the surf rise from the rocks, high into the air, white and forbidding like a living thing.

As the moon swung over its zenith, I could make out the little huts and trees on the island as in daytime and finally I saw a small fire on the beach, near where I judged the village to be. It was half-past eleven when I rowed up to the jetty, which stood out into the water like an immense centipede. The squeak of my rowlocks betrayed my presence and the natives, who were lying on the beach by the fire, rushed out onto the jetty. They had been waiting for me. Then came the usual babble of voices and torrent of questions.

Their curiosity was unappeased for I tied my painter to a sloop at anchor near the jetty and even as I was preparing to turn in, a native policeman drove the crowd inshore.

The Yakaboo was indeed a real "live-aboard-ship" and had my stove been in commission I could have cooked my supper in the cockpit. In fact, I could have lived aboard indefinitely as long as food and water held out, for I could rig up my tent over the cockpit in the event of rain. Cold meat, crackers, and cool fresh water made an excellent repast for a starved and healthy stomach.

One who has never done this sort of thing can scarcely appreciate my sense of complete luxury as I lay in my blankets in the snug cockpit of the Yakaboo. And always at the mention of the Yakaboo I think of her as a thing of life. There was scarcely any motion in the quiet waters of the bay, yet I could feel her buoying me up, as though I were resting on a small cloud suspended in midair, a Mahomet's coffin. Then as I rolled over to lie on my side she would give gracefully-she was always there under me, holding me up out of the sea-my water cradle. A great contentment came over me as I lay contemplating the magical harbor into which I had found my way like a tired gull.

I had hardly fallen asleep when Walker sailed alongside and awoke me. He had lost track of me in the darkness and had been looking for me till the moonlight had shown the Yakaboo crawling into Admiralty harbor. He sent his two men ashore and I passed him some food and one of my blankets. He left again at five in the morning with some food which I insisted upon his taking and a better opinion of the ability of the Yakaboo. There are few men I should care to have with me in the open. Walker is one of them.

With the sun came the incessant babble of an increasing crowd on shore. Sleep was impossible and I landed at nine o'clock. Before I had turned in the night before, I asked the crowd whether "Old Bill" Wallace, the Nestor of whalemen in the Grenadines, was still alive. Yes, they told me, he lived in the hills beyond "Tony Gibbon's."

"Old Bill" came down as I was cooking breakfast over a coalpot in the parsonage. (When I end this life I shall go with an infinite debt to lighthouse keepers, Scotsmen and English parsons.) I gave him a letter I had carried from Boston in my portfolio. It was from a shipmate of his son, who had been lost at sea. In it were two photographs of young Wallace on the next but last of his voyages, showing his active young figure at the "mincing" board and in the cross trees. As the old man opened the letter a look of surprise came over him and he held the photographs in trembling hands. It was like a message from the dead, almost, to see his son at work on the whaler, and a far-off look came into his eyes as he stood there, brought back so suddenly to the vague tragedy that had been the hardest burden of a hard life.

"Old Bill" and the skipper of the Yakaboo.

"I am old and broken down now, and not much use," he said, "but as long as these old hands can work I'll keep on going till I slip my moorings and get off on my last cruise." Hard work and a rough life had been the lot of this relic of a fast vanishing type of deepwater sailor. In that romance age of fifteen he had spewed the silver spoon from his mouth and left it on the hearth of his Scotland home to taste his first sting of bitterness under the care of a Yankee skipper.

He finally drifted to Bequia with his earnings and bought a large sugar plantation. But the seafaring man rarely prospers on land. The failure of sugar cane in the islands, followed by a disastrous hurricane, brought an end to his few years of ease, and he had to turn to the humpbacking that he had taught the natives, "jumbie crabs," he called them. Now, too old to go whaling, he is rusting away like the ships he used to sail, waiting to "slip his moorings."

In the afternoon, I climbed the hill to his house, rebuilt in a corner of the ruins of his former home, as if backed off in a corner by fate. There I met his blue-eyed little wife and drank with them the bitter tea that had simmered on the coals since morning. It was many years since he had talked to one from the States and as the afternoon grew old his enthusiasm over the adventures of his life rose to the fitting climax of a hurricane off Delos in Africa.

The rickety chair would no longer hold him and he stood in the doorway, dark against the levelled rays of the setting sun, a fiery, Quixotic figure, brandishing his cutlass to illustrate how, as a mate on the almost doomed ship, he had stood years ago in that tense moment with uplifted axe ready to cut the weather shrouds. She was "six points higher than Jordan," he had thought, as she lay with her lee rail under water, not a rag up, held by the force of the wind against her spars. Then -- "be th' powers o' Malkenny's cat," she had righted herself and the ship was saved without losing a stick. I can feel his enthusiasm now and I wonder if, in the eternal fitness of things, the good saint will promote him to captaincy on the ghost of that ship on the seas of the world to come.

There was a pathetic touch in his farewell to me, for I had brought back to him the sweet memories of a gallant son. I left him still standing in the doorway, the cutlass hanging forgotten from one arm, the other around the shoulder of his mild little wife.

One hears a great deal of the tropical sunset, but to me there is nothing to compare with the moonlight of these islands, and it was a continual source of pleasure to wander about in the hills in the light of the full moon. There is a color effect that I have found in no other place. The blue sky as in daytime, but softened, with the motion of the large, white, fleecy clouds in contrast. The sea a darker blue with the pattern of the coral reefs showing up yellow and brown. The island itself a subdued blue framed in the thin line of white foam on the rocks. Distance was here and as I stood high above the bay I could see the islands I had left, Cannouan, Mayero, Union, high and dark, and even Carriacou, thirty miles away.

On my way down to the bay, I passed a group of little native huts, where a more or less heated discussion was in progress.

"He no sail in de da' -- he floy in de noight! You tink dat li'le boat go in de water? Oh, my!" and I realized that I was the topic of conversation. As I neared them, one said, "O Lard, HE come now."I now understood why I had been so quickly discovered when I rowed into the harbor the night before. One of the natives, with a powerful ship's telescope "obtained" from some Yankee whaler, had picked up my queer rig, late in the afternoon, as I was approaching Bequia and had seen my sails go down shortly after sunset. They knew that the wind was dropping and they believed that I had spread out my sails parallel to the water and flown. In fact, the common belief in Bequia was that the sailing was only a bluff and that I really covered my distances by flying at night.

So they had built a bonfire and were waiting for me on the beach, where they knew I would land. Sure enough, I did land there, but before they had had a chance to see me fly, I had folded the wings of the Yakaboo and was rowing. They could not understand how such a small boat could live in their seas. The cut of the sails suggested wings and the natural deduction was, "He no sail, he floy."

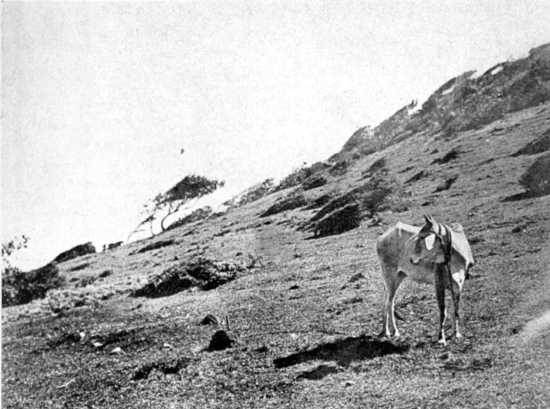

The effect of the trade wind on the vegetation, Bequia.

I was a man apart and I found out later that the natives regarded me with a great deal of awe and thought that I carried some sort of imp or fetish with me in the canoe. Perhaps I did. Was there not a gru-gru nut the postmaster at Goyave had given me, and how about my little dead mascot? Except for the more intelligent men, they were afraid of me, but curiosity would get the better of their fear and as I talked to them I would now and then feel the furtive fingers of some of the bolder ones touching my clothes as one would a priest's robe.

It was one afternoon, while I was visiting a "tryworks" on the south shore, where they were boiling oil from my friend the porpoise, that I espied a little boat with a peculiar rig coming down from the East. The natives confirmed my guess, it was a Carib canoe. By a lucky chance the canoe beached almost at my feet. There were four Indians in her and I immediately questioned them as to the settlement at Sandy Point, on the north end of Saint Vincent. Yes, they were from the Carib Country and would be glad to have me come up and live with them as long as I wished. What a joy it was to see the lighter color of their skins, their straight black hair, and thin lips. They reminded me of the Japanese and my eye did not miss the ease with which they carried themselves and handled their canoe.

The next morning I said, "Yakaboo," to the Grenadines and laid my course for Saint Vincent and the Carib Country.